Posts Tagged ‘process’

The First Fathers’ Day Without Dad

By Richard D. Quodomine

When you lose a person in the generation before you, you begin to think about what they meant to you. When you lose a parent, you think about all they meant, and you hoped you either lived up to the best of yourself, or in some cases where the parenting was not as instructive or kind, you hope you’ve raised yourself beyond difficult circumstances. If you’re fortunate, Dad pushes every endeavor and delights in your successes and constructively scolds you when you fail without ever making you feel embarrassed or willfully stupid – unless of course, you were actually willfully stupid.

Did we have our differences? Absolutely. My father was more conservative than I am politically, though he rejected hateful politics and would not vote for it. We come from a mixed religious family, and my father was Christian, I am Jewish. We had philosophical differences and we approached life differently. But we also valued accomplishment, kindness for its own sake, and service in the public good. He is part of the reason I have chosen a career in civil service. I believe government can and should serve at the behest of its citizenry, and while he mistrusted government intrinsically, he had respect for my approach in working for it.

As part of my research in the public interest, I went to India for a conference. While en route, somewhere between Zurich and Delhi, my Dad suddenly passed from a cardiac arrest. I couldn’t return home for several days, so I soldiered on without telling anyone at the conference. I figured the way to honor his memory was to do my very best. He was gone – and weeping in my hotel room wasn’t what he would have wanted.

Dad had a heart condition, but he had had corrective surgery and was otherwise in outstanding physical shape for his age. He was my Mom’s primary caregiver. This was especially tragic because she has dementia. Sometimes, I get angry that Dad is gone because the burden is much greater on myself and my family. Sometimes, I am so grateful that he gave me the strength to help care for Mom. Most of the time, even months removed, I’m just missing talking to my Dad.

The first father’s day without Dad is the hardest, or so “they say.” I think that is true, but it’s harder not because I am sad, but because there’s nothing that can replace all that he was. It’s trite to say “he lives in me.” I think it’s better to say “I take what he has given me, and I will grow and make this life my own.” I don’t think anyone should strive to be “just like” their parent. They should strive to be their own authentic selves, using the best of their parent as the cornerstone, not the ceiling. In Judaism, we say “May their memory be for a blessing” as a condolence. Dad’s memory is, for certain, a blessing.

Lyss – Therapy and the right fit

Lyss – Therapy and the right fit

Lyss talks about therapy and finding the right fit

There One Day and Gone the Next : Art Therapy and Grief

By Sarah Smith DTATI, BFA

Over the last 12 years or so, I’ve had the opportunity to work with those grieving individually and in group settings, which has provided me with experience and insight into how art therapy (and art as therapy) can be beneficial to those dealing with loss.

What is Art Therapy?

“Art therapy combines the creative process and psychotherapy, facilitating self-exploration and understanding. Using imagery, colour and shape as part of this creative therapeutic process, thoughts and feelings can be expressed that would otherwise be difficult to articulate,”(CATA, 2022).

There’s no right or wrong in art therapy, it’s a matter of using the art as a vessel for wellness along side a trained professional. There are many benefits one can receive from engaging in the art making process such as: healthy coping strategies, insight, emotional stability/balance, stress /anxiety reduction, grounding of emotions, pleasure/joy, creativity, safe space, expression, control, freedom, and connection among many others!

Art Therapy and Grief

Grief is a very layered and challenging thing that is unique for each individual who experiences loss.

Because there is no “proper” way to grieve, art therapy can make for an excellent coping strategy as it allows for each person to express themselves in the way that’s best for them.

Unlike traditional “talk therapy”, art therapy has the art, so this means that one does not need to speak if they don’t want to or if they cant find the way to articulate how they feel into words. Sometimes, while people are grieving they cant even pin point how they feel and at other times the emotions can just be so overwhelming it can affect one physically and to try and talk about the emotions just exacerbates them.

Creating art in itself can be a healing thing. It can be a fun or relaxing thing to do. Engaging in an art therapy session can allow for so many more benefits. The art therapist can provide the participant with specific art therapy directives and art materials that they feel may be beneficial to your needs. Art therapists are trained to read and assess clients’ artwork. This means they may see things you may have missed that you might benefit from if brought to your attention. This insight makes it a great learning tool for self-discovery. We as art therapists believe that the art work holds the subconscious. What’s great about this for those who are grieving is that people can process however they need to. Some people need more time to process, some people need a more gentle approach where they feel in control, some people refuse to acknowledge things, and some people are just going through the motions and engaging in the art making process. The subconscious is purging and the healing is happening whether they realize it or not.

Art Therapy Directives (examples)

I facilitated a workshop at a hospice a couple years ago and offered it to those who had lost a loved one. The workshop began with a few art therapy warm-up exercises with the intention of helping everyone feel a bit more comfortable in the space and with each other.

The first art therapy directive I had them do was make flowers out of coffee filters, markers, and water. I wanted them to make something symbolic for their loved one. They began by writing whatever they wanted onto the coffee filters. Some people wrote the persons name, poems, a memory, or even drew a picture. They then watered down the filters and the colours began to bleed. Some people cried during this part. They could resonate with the symbolism. The water like tears. The bleeding of the colours representing pain, fuzzy memories, and a distant grasp on the person. When the coffee filters had dried we had turned them into flowers. The transformation of taking what we lost and carrying it forward in a new way was very powerful to witness and a very healing thing to say the least.

The second art therapy directive was focused more on the individual rather than the deceased. I gave everyone a mask. I instructed them to paint the front of the mask how they appear to the world and I asked them to create on the inside of the mask to show how they really feel or how they are actually doing (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

They shared their art work from the workshop, but it was heavy. They were feeling sensitive and tired among other feelings so I had them sit and talk for a bit and then had them pull a self-care card for a distraction before letting them and drive home, as it may not have otherwise been safe for anyone overwhelmed after such an engaging session. This is typically how I run a grief workshop. Before they left the hospice asked them to fill out a score sheet to see how they felt about participating in the workshop and everyone said they liked it and for reasons, such as that they felt less anxious, they felt less alone, the felt lighter and more hopeful after the workshop.

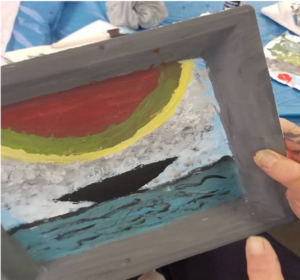

At another hospice art therapy workshop, I had them create memory boxes. I provided them with a wooden box along with a variety of art materials, the only thing I asked was that they brought in a picture of the person they had lost. The purpose of this was to give them an opportunity to create something that could hold two energies, a place to honour them deceased, but also something tangible for them to have and hold. From my observations, I remember them taking a lot of time on these boxes and they were very quiet while making them. When they shared them, they were emotional, of course, but pride came through, it was like they made them for their people and wanted to make them well, so that their loved one would really like the box. This made them feel good for reasons such as honouring the person still while they are gone. Some people felt that their guilt had been eased a bit because they were physically doing something for that person who was no longer here. To see an example, see figure 2 and 2b.

Figure 2

Figure 2b.

Following the memory boxes, I had them paint a step by step painting for their loved one. This was more of an art as therapy approach. This means they were literally using the art itself for wellness. They followed along with me and painted a whole painting. By following me, they were able to safely let go and get lost in the art making process. The intention was to enjoy the process while also giving them a healthy mental and emotional escape for however long it took us to paint the picture. I selected a picture of trees that had no leaves, purposely to symbolize letting go, loss, and reflection but the painting had an element of hope to it, the tress were pointing up to the sky, facing the light and there was lots of colour (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

The photos below are some examples of art from some of my sessions with clients around grief. They speak for themselves.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

When Death Feels like a Thief

By Amanda Sebastian-Carrier.

Amanda Sebastian-Carrier is a communications professional who writes about her grief journey as a form of healing.

Thief!

Oh, how loudly I’d yell the words, shaking my fist at its back as it ran from me through the crowded bazaar. You would find me, soaked in tears, panting and crying and trying to explain that something very precious had been taken from me by that, that, THAT THIEF!

In the heart of my grief, at my frailest, all I could see was what was no more. I grieved all that was stolen from me by death; love, security and even my very self. Had I known the value of having every pocket of who I was, picked bare by grief, I would not have fought so hard to hold onto it all. I’d have let that cutpurse have it all without raising an alarm. That egg, it could take the golden globs of joy, the silvery wisps of laughter and the precious stones of delight that once filled my world and sell them all to the highest bidder. How could I have seen the faceless bidder, behind their paddle, was me. Grief, that panderer, was only taking from me what I could not currently carry and would sell it back, piece by piece, as the currency of healing was paid.

If only I’d had a clue that the larceny committed by grief was not the crime I was reporting, I’d have stopped much earlier. Before death, I had no idea that the theft of all you knew and love and the process of reclaiming your sense of security and self were a process that had the ability to change your life forever, but not how you might think. Grief and mourning can lead to healing if you do the work. If you don’t waste time filing reports to the universe about the misappropriation of your loved one. If you immerse yourself in the process of mourning, instead of decrying the looting of your life. If you truly, honestly, and mindfully, say goodbye instead of trying to hold on. If you can do all that, the only thing that grief is able to steal is your pain. You just have to be willing to give it up, let it be taken.

It’s only now, after I have made my peace with the plundering pirates of grief that I can see what I saw as theft, was actually a gift. The thief that is grief was not stealing all that was happy and good in my life, it was stealing my pain. Grief sat on me, taking all the things I didn’t know how to process, and filtered them through different lenses. It sat with me, taking from me each tear that fell, each shaky breath and each battered heartbeat. Grief took all I had, each story, each memory, and each emotion from me until I began to have room to process life again. Grief took, not a life in the way death had, but death; out of the way of life. Death stole life and grief; grief gave it back.

Weathering the Intense Emotions of Grief

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

Grief often comes with powerful, unpredictable emotional shifts that can be painful to experience. While it’s important to find ways to sit with these feelings, to acknowledge the pain of grief and accept loss, it’s also necessary to find ways to ease and manage the pain. There are several simple activities that you can explore to help.

Ground Yourself in the Present

Use your senses to remind you that you are safe, here and now. When we are feeling intense emotions we are often caught reliving a moment in the past, or we are fretting over some anticipated event in the future. We can’t undo the past and we can’t control the future, which only intensifies these difficult feelings. When you use your senses, it pauses your racing thoughts and can help calm the turbulent feelings.

Notice the things in your environment you can see. Count the number of items that begin with the letter A, then the letter B, or count the number of green things.

Notice what you feel around your body. Sense the ground under your feet, the chair under your bottom, the clothes against your skin, the sun on your cheeks, or the breeze in your hair.

Notice what you hear. Voices. Background noises of the building such as the furnace or a fan or the hum of fluorescent lights. Music. Nature sounds.

Notice what you smell. Is the air stale or fresh? Is there some overpowering smell, or not much smell at all?

Notice if you have a taste in your mouth. Is it the sweetness or savoury taste of something you just ate, the minty freshness of toothpaste or gum, or perhaps the sour taste of morning breath.

Breathe.

A deep slow breath can activate the calming centre of our nervous system. When you breathe deeply and exhale slowly, you set off a cascade of calming chemicals in your brain that help ease tension and stress.

Try 4-7-8 breathing. Inhale as you count to four. Hold your breath for a count of seven. Exhale as you count to eight. Repeating this breath three times takes less than one minute, and when you practice it often you develop a muscle memory that helps you access this deep, slow breath during times of strife.

Indulge in Self Care

Enjoy a cup of your favourite herbal tea or soup. Take a hot bath, perhaps adding Epsom salts. Or a shower with your favourite body wash. The warmth and scent of these activities will work together to activate the same calming centre in your nervous system that is affected by deep, slow breathing.

Plan Intentional Change

Sometimes our routines cue us to experience distressing memories and disturbing thoughts and feelings. When this is the case, it can help to examine your schedule and activities. What seems to upset you? Is there a way to pause the activity or shift it to another time of day to try to break the connection with the difficult experience?

It’s true that we can’t help our thoughts and feelings. It’s also true that we can develop responses to the experience of intense grief that help us feel more in control as we heal.

Tending to My Garden of Grief

By Taylor Bourassa, RP & Professional Art Therapist.

Losing a loved one –whether through death or the end of a relationship, brings up complex emotions, some of which are hard to process. The first major loss I can remember experiencing was when I was quite young and my grandfather died. I barely knew the man, but to this day we still share stories of his impact on my father, his son, my mother, his daughter-in-law, and us, his grandchildren. The memories bubble up slowly and play in my mind like a distorted movie playing on the television screen. It is part of my life I can’t quite recollect without the input of others. Then in my middle teen years I attended a funeral for my grandmother’s sister, and I remember watching the grief flood my grandmother’s face as she dissolved into tears and I wondered: how can I, or any one else hold this grief in the “right” way? How can any of us help ease that pain?

When I was 16 or 17, my cat, who I still recognize as my earliest best friend, developed cancer and needed to be put down. This was the hardest thing I had had to face at that point in my young life. I was faced with what seemed to be inconsolable grief. That same thought bubbled up: how can anyone ease this unbearable pain?

A few years ago I was faced again with the reality of our mortality on this planet Earth when my dog, Roxy, had to be put down due to ailing health and decline. That same question flitted through my mind. Now, at 29, and having faced multiple losses and deaths I finally have some semblance of an answer to that question. It isn’t straightforward, and it probably isn’t universal. But it feels appropriate for me: remember, honour and celebrate. The pain of these losses will more than likely be with me my entire life, until the day I die and pass the pain onto my loved ones left behind. So long as I remember the lives of those I have lost, honour their presence and impact on me and celebrate their spirit, they will continue to live with me and the pain will feel bearable. It will no longer stop me in my tracks. Instead, it will encourage me and propel me forward through the transmutation of that grief into something different, something more nuanced and fluid. I’d like to share a practice for processing grief which I have found to be especially helpful.

Reflect on person or pet that has passed on and write a letter to them. Use recycled, bio-degradable paper to write this letter, so that when you get to the end of this invitation and you plant your letter it will be taken back into the earth and soil.

Imagine the things you appreciate about this person, the memories you two share, the impact they have had on you, and anything you feel has been left unsaid or unexpressed while they were still living. Before you close and seal the letter, read it back to yourself and sit with whatever memories, feelings and thoughts come up. Allow the energy of this person to show up and sit with that felt sense of who they were. When you are ready, fill the envelope with your letter and the seeds of your choice: flowers, fruits or vegetables. Use the seeds which you feel best honours the person. Find a location that is both accessible to you and reflects a space of honouring and celebration. This may be a favourite shared space between the two of you, or a new spot you would like to crop out as a way to honour and remember them. Once you have found your spot, take your letter and your seeds and bury them in this spot. Eventually, the seeds you have planted will sprout and grow, changing the spot into a new gravesite garden. Soon, the biodegradable letter will also be gone, subsumed back into the womb of the earth and soil, feeding the land for the growth and propagation of the flowers you have planted. Maybe these flowers will remain only in the space you created, or, what is more likely, they will be spread on the wind and the legs of bees, and the beaks of birds until the grass beneath is forever changed, peppered with new and continuing growth.

What a beautiful way to honour the deceased: recognizing their continued impact on you and the world around you as they and their memory connects with and returns to the earth. I find this to be a helpful way to process my own grief because it allows me an embodied, tangible and somatic way of addressing, honouring and processing the grief held inside my body. The grief will always be there in some capacity, and now there is a space which I can visit and reflect. The heaviness and weight of the grief is no longer mine alone – the whole earth helps me to carry it. Grief is such a unique, yet universal experience. My own experiencing of grief is all I know for certain, and so I keep searching for answers. I hope that as you navigate your own grief, you can alleviate some of the weight by sharing the load with the natural world around you.

What I know about grief

Post by Alyssa Warmland, artist, activist, well-practiced griever.

I earned my “grief card” at 15, when I lost my mother. Since then, I’ve experienced other instances of loss and have become a well-practiced griever. Most recently, I lost a friend in a tragic way. She was deeply connected within our rural Ontario community and as I grieve her loss, I’m watching many other people around me grieve. Some, like me, are experienced in grief. Others are newer to the experience.

The following are some things I know to be true about grief for me, based on my lived experience. Some of them may resonate with you as well. Grief is unique to the people experiencing it in each moment, so please take whatever makes sense to you from this share and leave whatever doesn’t.

– Give yourself space to just feel the waves. Sometimes it feels like it’s not quite so intense, and then sometimes it feels like you’ve just been punched in the stomach. And it’ll cycle around. And it won’t feel this way forever.

– You’re totally allowed to feel whatever it is you’re feeling. Last night, while I spoke with sobbing friends on the phone, I was absolutely furious. Today, it’s that gut-punch feeling. it’ll cycle around. And it won’t be this way forever.

– Sharing stories can be helpful. Celebrate the reasons you loved whoever you’re grieving. Look at the pictures. Watch the videos. Sing the songs.

– Be patient with yourself, but keep going through the motions of what you know you need to do to maintain your wellness while you grieve. Eat something, even if you’re not hungry. Sleep or lay down, even if you feel like you’ll never fall asleep (podcasts can help make it less overwhelming). Drink water. Go for a walk outside. Write about it. Work, if you want to work (and plan for some extensions on stuff if you can, so you can work a bit more slowly than usual if you need to)

– Your brain may take a little longer to process things. Your memory may not work as well. You may feel irritable or overwhelmed. It’s okay.

– If the death part itself was hard, try to avoid focusing on the end, and instead think about the person you loved and who they were when they were well.

– Connect with other people who are grieving, it may be easier to know you’re not alone.

To learn more about collective grief, please read Maureen’s post on the topic.

Helping Others Help You Through Grief

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

When you’ve experienced the death of a loved one, one of the most difficult things you will go through is trying to find out what helps you adjust to the loss. This can be compounded when others around you don’t understand what you’re going through, and don’t know how to help you. Although you may not have much energy, and you may be reluctant to become a teacher, it may be just what your family and friends need to help you through your grief.

The concept of “pocket phrases” can be quite useful in helping others learn what you need as you grieve. These are statements that you practice ahead of time so that they come to you effortlessly in the moments when you are upset but still need to ask for someone’s help or understanding.

“That’s not helpful.” Usually, our friends and family are trying to help, however their actions may have the opposite effect. With practice, you can develop the ability to say this in a calm, confident voice that halts comments or behaviour that you find hurtful.

“Grief isn’t easy, but it is necessary.” Well-meaning people sometimes want us to move through grief quickly when that is just not possible. You can remind them that it’s normal to feel a full range of feelings after a loss and you don’t need to ‘cheer up’.

“I’m adapting. It takes time to adjust.” When someone in your circle of acquaintances asks how you’re doing, you can use this phrase to remind them that grief is a process. You can ask them directly to have patience with your intense feelings, the changes in your routines and at the same time let them know you’ll never be quite the same again.

“I’m not strong. I’m just doing what I must.” This phrase can be helpful when people praise your ability to function in routine tasks and situations. You may want them to understand that although you may look well on the outside, there’s still a whirlwind of emotion and distress raging unpredictably inside you.

“I like it when you say their name and we talk about them.” You can let people know they don’t have to be afraid to mention your loved one. If you want to share stories, and hear stories from others, you may need to give permission with a clear, direct statement such as this so that people aren’t afraid they will hurt you more by talking about them.

These sample statements can be a good starting point for developing your own useful “pocket phrases” to help teach the people in your life how to help you as you grieve. Remember that the more you practice the things you wish you could say, the easier it will become to pull them out in a peaceful and positive way when needed.

Jane – My Story

Jane – My Story

Jane shares her story about losing two of her grandparents just before the pandemic and the ways the pandemic has impacted her ability to process grief.

Jane – Loneliness while processing grief

Jane – Loneliness while processing grief

Jane talks about grieving without her extended family because of the pandemic and how that’s impacted things like scattering ashes and having celebrations of life.

Jane – Struggling to process layers of grief

Jane – Struggling to process layers of grief

Jane talks about her experience navigating multiple losses in a short time and the impact the pandemic has had on that by adding even more multi-facitated layers of grief

Jane – What processing grief during the pandemic may look like

Jane – What processing grief during the pandemic may look like

Jane talks about how the pandemic has postponed a lot of “firsts” without her grandparents that have impacted her experience of moving through grief.