Posts Tagged ‘pet loss’

Things That Helped When My Dog Was Dying

I lived with a dog named Althea, who belonged to my roommate, during my undergrad. Every year, my partner, our roommate, and I would go to a summer solstice festival. The year Althea was pregnant, my roommate brought her to the festival. The first night there, he retired to his tent to nap in preparation for the evening’s festivities, and my partner and I walked with her around the festival grounds. I noticed her water break and we had a friend fetch our roommate while we took her to his car, a small place we knew she felt safe. She gave birth to eight puppies that night, as the sky opened and rain poured from the sky.

I remember catching the puppies, one by one, letting Allie clean them, and then handing them to my partner to hold in a towel while she birthed the next. Luna was the sixth puppy born. She had a white-tipped tail and a white crescent moon marking on her forehead. She was the smallest of the litter, but not by much. I knew immediately that she was for me, and I for her.

Over the next few years, Luna was by my side while I finished my undergrad, kicked my doctor-sanctioned opioid addiction, and moved to a new community. She couch-surfed with us during a brief period of homelessness, came with me to my first big business job to sleep under my desk, greeted me exuberantly when we brought our son home from the hospital, and hiked hundreds of kilometres with my son and I during the pandemic.

The first sign she was unwell was that she was panting a lot. Then, she started having accidents. I took her to the vet, expecting an antibiotic for a UTI. But our vet did an x-ray and discovered a large tumour. She told me that our girl was in pain and only had a few weeks to months left. I was shocked, and so was my partner when I shared the news. It was his first real experience with grief, but I was a seasoned professional. We both spoke with therapists and chose to try to make the end of her life as good as possible.

I was tortured with the idea of choosing to euthanize her. I didn’t know how or when we would be able to make that call. My therapist told me that she had lost a dog the same way and that the day would come when she would look me in the eye and I would know it was time.

These are three things that helped:

1. Connecting with a therapist, my partner, and my peers who could relate.

It helped a lot to feel like other people in my network could relate to what I was going through. It felt so heavy and it helped to talk about it and to know I wasn’t alone.

2. Taking her to an indoor dog pool to do her favourite thing.

We wanted to honour her things that we knew brought her joy. Luna loved chasing balls and swimming in Lake Ontario, but it was too cold to take her to the lake. So we found an indoor dog pool and took her weekly. It seemed to help with her pain and it helped all of us to find joy amidst the sadness.

3. Stamping her paw prints.

I ordered a baby footprint kit online and stamped her paws. I framed one and hung it on our living room wall. One day, I hope to get it tattooed.

Finally, the day came when, just as my therapist had told me would happen, Luna looked at me and I knew she was in pain and didn’t want to suffer anymore. We made it through a heartbreaking night and drove her to the vet as soon as it opened in the morning. I told her she would feel better soon. She leaned into me, I held her, and my partner and I both told her we loved her and thanked her for everything she had brought to our lives.

It was the purest love I have ever known and lost. And it was an experience I know so many people can relate to. I believe that grieving her after her death was a little bit easier because I knew we had given her a good life, complete with an excellent life at the end. I think about her often- on the trails, at the lake, as my son grows, and as I prepare to welcome another baby she won’t dance as she meets. Holding space for pet loss is valid and important. It is a type of grief worth making space for.

____________________________________________

Alyssa Warmland is an interdisciplinary artist and activist. Her work utilizes elements of radical vulnerability, restorative justice, mindfulness, compassion, performance, and direct action.

She is a mother, La Leche League Leader, Board member of La Leche League Canada, writer, podcaster, producer, director, performer, content creator, not-for-profit administrator, and abstract visual artist. Lyss is a strong advocate for fumbling towards an ethic of care, especially when it comes to the topics of birth, matresence, and grief. Most of all, she’s interested in the way people choose to tell their stories and how that keeps them well.

Pet Loss: When People Fall Silent

A few days after the birth of my younger brother, my father was taking the dog he and my mother adopted from the humane society, along with my twin and I, to the veterinarian. Years later, my father would share how many times he wiped his eyes on the car ride there. Yoda shared 16 years of her life with my parents. She was there when they went from a family of 3 to 5, and at my mother’s side as we were preparing to welcome our younger brother.

Clifford was just under a year old at the time we said goodbye to Yoda. He and my mom were thick as thieves. He’d keep her company while we were at school, dad was at work, and in her most difficult moments as her cancer progressed.

Clifford was about 9 years old and had a history of health complications before my mother’s death. After her death, we knew he was grieving too. He would search her out, but he began to slow, and other health factors started to creep in. We were just starting to thaw out from the depths of our mother’s death. And now another loss six months later?

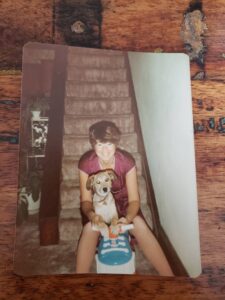

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Both are sitting on the stairs Jessica’s mother is smiling for the camera holding Yoda in her lap

Why do we question ourselves, and our grief when it comes to pet and other animal losses? Grief is the natural response when we face the loss of something or someone we have a connection to. The grief we feel after a pet dies is a natural response to their loss given the unique relationships we have with our pets. The humans in a pet’s family may be the only ones they know and love in their lifetime. We can experience grief bursts as we navigate this loss: instead of our grief showing up when our loved one no longer walks through the door at 6:00 pm after work, it may be each time we come home and don’t hear their paws hitting the ground as they race to greet us.

Roxy was our first dog a few years after Clifford and my mother’s death. It also felt strange: excited to have a dog again, while also feeling pangs of grief for Clifford. We can hold space for new love, while also still experiencing moments where we miss our old pets who we loved just as equally.

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

When Roxy was 13, our vet had noticed changes in her health typical for a dog her age. Every time I came home to visit I’d savor my time with her, and wonder, “Would this be the last time?”. A year later, Roxy was now no longer eating or drinking as often, and the vet felt her decline was her way of telling us she was ready to go. She indulged in poached salmon for her final dinner. Early one summer afternoon, my dad sent our family a photo of him lovingly holding Roxy in his arms and looking into her eyes. The note said she had passed onto the rainbow bridge, and he gave her extra hugs from all of us. I held space for the relief that she was no longer in pain, and the grief that I would never give her a belly rub again.

These are just some of my stories, and those reading this may have stories too. The tales where they did something ridiculous. The time they were there for you in your highest highs and lowest lows. The first time you met them. The last time you held them.

It’s important we hold space to share our stories but it can be difficult when pet and animal loss is a form of disenfranchised grief. Disenfranchised grief refers to when society denies a griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. This can leave us feeling even more isolated as we grieve. North American settler culture tends to prioritize human death loss over animal loss. But that doesn’t make your grief any less valid. Your grief may come in waves, be gentle with yourself as your body goes through this natural process.

You may experience shadowlosses and secondary losses related to the death of your pet.

I felt a pang when I didn’t hear the clinking of Roxy’s dog tags, expecting her to slowly saunter into the hallway my first visit back after her death. My parents felt lost with what they should do with pet care supplies they couldn’t donate. Many friends where I live have pets and I was able to share some of Roxy’s most treasured items with them, something Roxy would appreciate. But the choice tugged at my heartstrings as I removed these items from my family home.

Each unique bond with our pet is carried within us and you are allowed to honour it in whatever way makes sense. It may be having photos of your pet up in your space. Honour old traditions of your old pet with your new pet – if or when you choose to welcome a new pet into your life. Share stories of your special furry, feathered, fluffy, or scaly pet with your circle. Our stories can help us feel connected to them, and also feel less alone in our grief.

There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

______________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.