Posts Tagged ‘Loss’

Ripples of Grief: Supporting Ourselves, Others, and our Communities After a Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

When death knocks on the door of a community, each of us are impacted. Sometimes a death will touch many lives across a community, whether people knew the deceased personally or not. We may grieve the death of a family member, friend, or acquaintance, a well-known community member, or someone we are linked to by age, location, circumstances, etc. Community grief can feel overwhelming – we must tend to our own grief, but others in our life are grieving and hurting too. Each person in a community will grieve differently depending on their relationship to the person who has died, their own prior experiences of loss, and the unique coping strategies they rely on in grief.

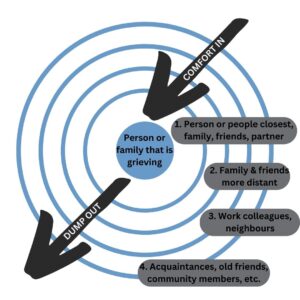

Developed by psychologist Susan Silk and Barry Goldman following Susan’s experience with a health crisis and her diagnosis with breast cancer, Ring Theory helps us learn how to support others and ourselves when a community death occurs.

Like a ripple on water when we drop a pebble into it, imagine a series of concentric circles. Those directly impacted by the crisis or death are in the innermost ring, with each outer ring consisting of those further removed from the crisis or death. Generally the immediate family, or those who lived with the deceased,are in the innermost ring, with close friends and other family in the next ring, co-workers and acquaintances in the next ring, and those in our greater community in the outer rings.

When someone experiences a death, those in outer rings pour comfort in, while those in inner rings are allowed to “dump” their thoughts or feelings out. When someone in an inner ring is dumping out their feelings, those in outer rings can show up with acceptance and care, listening and validating the person’s experiences.

Pouring comfort in can also be the offer of specific, practical help. This approach seeks the griever’s consent to accept specific support and comfort, it lets the griever say yes or no to the offer, and can confirm what kinds of support are most helpful to them. It’s important to offer support on the griever’s terms.

When a community faces loss, many who are impacted want to share their feelings about the loss. Susan recalled during her cancer treatment how some folks she did not have very close relationships with in her community would show up unannounced, forcing her to accept support, or people would talk about their own feelings about her diagnosis. Dumping feelings onto someone in an inner circle is not helpful. It can leave those experiencing the loss most personally as if their loss is unacknowledged. When we know which ring we sit in after a death, we can connect to our own outer rings anytime we need to tend to our feelings of grief. If we find ourselves thinking about reaching out for support from someone who is in an inner circle compared to our relationship to the deceased, we should take a step back. Is there someone else that may be located in the same ring as us, or someone in a ring outside of us that we can reach out to instead? Sometimes actually drawing out the rings of folks in our own life impacted by a death can clarify where we need to support others, and who we can connect with for our own support.

Whether supporting others, or seeking support ourselves, a helpful phrase may be “Would you like to be heard, helped, or hugged?” Being heard means receiving supportive listening and validation. Being helped may mean brainstorming and collaborative problem-solving, or providing specific practical help with tasks. Sometimes there are no words or help we can offer, but, if welcome, our steady presence and a comforting hug can communicate our support.

Each person in a community will be impacted differently by a community death. It’s important to remember this theory about who we need to pour comfort into, and who we ourselves can dump out to as we navigate a community loss.

Articles Reviewed for Blog Post:

https://karenwulfson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/How-not-to-say-the-wrong-thing1.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-xpm-2013-apr-07-la-oe-0407-silk-ring-theory-20130407-story.html (actual article in LA Times first written by Susan Silk – first link is PDF version of same article)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201705/ring-theory-helps-us-bring-comfort-in

The First Fathers’ Day Without Dad

By Richard D. Quodomine

When you lose a person in the generation before you, you begin to think about what they meant to you. When you lose a parent, you think about all they meant, and you hoped you either lived up to the best of yourself, or in some cases where the parenting was not as instructive or kind, you hope you’ve raised yourself beyond difficult circumstances. If you’re fortunate, Dad pushes every endeavor and delights in your successes and constructively scolds you when you fail without ever making you feel embarrassed or willfully stupid – unless of course, you were actually willfully stupid.

Did we have our differences? Absolutely. My father was more conservative than I am politically, though he rejected hateful politics and would not vote for it. We come from a mixed religious family, and my father was Christian, I am Jewish. We had philosophical differences and we approached life differently. But we also valued accomplishment, kindness for its own sake, and service in the public good. He is part of the reason I have chosen a career in civil service. I believe government can and should serve at the behest of its citizenry, and while he mistrusted government intrinsically, he had respect for my approach in working for it.

As part of my research in the public interest, I went to India for a conference. While en route, somewhere between Zurich and Delhi, my Dad suddenly passed from a cardiac arrest. I couldn’t return home for several days, so I soldiered on without telling anyone at the conference. I figured the way to honor his memory was to do my very best. He was gone – and weeping in my hotel room wasn’t what he would have wanted.

Dad had a heart condition, but he had had corrective surgery and was otherwise in outstanding physical shape for his age. He was my Mom’s primary caregiver. This was especially tragic because she has dementia. Sometimes, I get angry that Dad is gone because the burden is much greater on myself and my family. Sometimes, I am so grateful that he gave me the strength to help care for Mom. Most of the time, even months removed, I’m just missing talking to my Dad.

The first father’s day without Dad is the hardest, or so “they say.” I think that is true, but it’s harder not because I am sad, but because there’s nothing that can replace all that he was. It’s trite to say “he lives in me.” I think it’s better to say “I take what he has given me, and I will grow and make this life my own.” I don’t think anyone should strive to be “just like” their parent. They should strive to be their own authentic selves, using the best of their parent as the cornerstone, not the ceiling. In Judaism, we say “May their memory be for a blessing” as a condolence. Dad’s memory is, for certain, a blessing.

Mourning a Man I Never Knew

By David Newland

The following blog post is a reworking of a post originally written in 2005 under the same name on his website.

This spring, I turned fifty-four. I have now outlived the father I never knew: my biological father. It’s been almost twenty-three years since we spoke; eighteen years since I learned of his death. I’m still dealing with the strange grief of his loss.

As an adoptee, I always had questions about my origins that my loving, caring adoptive parents couldn’t answer. In my twenties, I applied to Child Services for more information, and after eight years of waiting on my part, they did a search in 2000. After some effort, they couldn’t find my birth-mother, but quickly produced contact info for my biological father. They offered to put us in touch.

After jumping through a few official hoops, we emailed back and forth a bit, and finally, we spoke on the phone, maybe three times in all.

I can’t even describe what that was like – intense, starkly honest, humorous and deep. Here was a man who had made most of the same mistakes I had, only far worse. Depression, drugs, divorce. Family problems. Anger management. Women. He hid nothing, as far as I could tell, although his stories sometimes conflicted.

I didn’t hold anything back either. I insisted that he honour my experience as an adoptee. It wasn’t easy for me, handling the big hole in my life. He had a hard time understanding that. He said his own kids had it a lot worse than me. He was right, but that wasn’t for him to say. I heard it from them.

It was good to connect, but I knew he wasn’t good for me. I chose not to pursue further connection. I knew he was out there. He knew where I was.

There was no contact for a few years. And then one day, in January of 2005, I found out he was dead. I was online at work, looking for some information on the original (Polish) spelling of his last name, and wham! the first thing that came up was a memorial page. He had died, nearly a year before, in March 2004, aged 54.

I never knew him in life. I still don’t know him in death. But I’ve been grieving him for a long time, in my way.

In 2016, still reckoning with the hole he left, I went to Red Deer to find his grave. I narrated that journey in a CBC radio documentary, The heartache and healing of finding my birth father. I never found a grave: only my own shadow over a four-by-four stake in the ground. I did enjoy a delicious steak sandwich at a local hotel restaurant he was fond of.

I’ve been back to Red Deer twice since then. The last time I went, even the stake was gone. And so was the steak sandwich, restaurant, hotel and all.

The picture on the memorial page linked above is the only likeness I ever saw of my birth-father. I always thought I saw my face in his. Now, having reached his age, I see his face in mine.

Reflections on Mother’s Day

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

The signs of spring start to show up: the bird calls, sleepy daffodils and tulips waking up from their slumber, the trees beginning to bud ready to shade us with their leaves all season. And then, the flood of Mother’s Day emails start crashing into our inboxes.

Mother’s day is a holiday where we show appreciation and care for the maternal roles in our lives. However, this holiday can feel very overwhelming for those of us who are grieving the death of a mother figure, a mother grieving their child, or those of us grieving the loss of not being able to become mothers ourselves. The ads, commercials, and displays at the store, designed to be appealing and inviting become a painful grief trigger as we go about our day, our minds and hearts going to the person we’re grieving who isn’t alive to receive their flowers or gifts. Feeling as if our grief is heightened on holidays or times of celebration is a natural reaction to have. Often around these times of the year we gather with our loved ones, and our special person’s absence feels amplified.

Over the years, my grief reactions around mother’s day continue to change. At first, it was like a black looming cloud and I would avoid anything to do with Mother’s Day. Over time, I still have had hard Mother’s Days but the day looks much different. I may write to my mother, choose to ignore the day and do things unrelated to Mother’s Day, make a comforting meal from my childhood, or participate in a memorial event on Mother’s Day. Regardless of what I choose to do, or not do on Mother’s Day I make sure to give myself the space and compassion to rest and recover – grief can be exhausting.

There is no right or wrong way to grieve, nor how to go through Mother’s Day. Our relationship as mothers and children is unique, so too will be our grief. The following ideas may be how you’d like to take time to honour the person you’re remembering and grieving on Mother’s Day:

-Unsubscribing from Mother’s Day emails (some companies have a special opt-out message for folks to unsubscribe from these types of emails)

– Ignoring Mother’s Day altogether and doing something that fills you up (it could be going to a movie your person may have never wanted to go to or taking a long hike)

– Creating an altar with photos, keepsakes, and favourite things of your person

– Lighting a candle in their honour

– Writing them a card, updating them on your life and reflecting on your relationship

– Creating a new tradition or ritual to replace Mother’s Day

– Packing your day with connection and activities with trusted others who support you in your grief

– Having a day of nothing: allowing yourself to do what your heart is telling you (a bath, a nap, a cry)

Sometimes our grief may feel heaviest in anticipation of Mother’s Day or on Mother’s Day itself. As we enter May and Mother’s Day approaches, I wish for you to be compassionate towards yourself and move through the day in the way that fits your heart and relationship best.

Nicole – Grieving as a community

Nicole – Grieving as a community

Nicole discusses the power of grieving together as a community. Finding connection and trust.

Grief & Ice Cream

By John (Lewis) Clark, Author of upcoming book (Cook Away Your Grief).

When my wife of 18 years died in 2016, I became a single father missing the love of my life, and also had to learn how to raise two girls (13-17 at the time) on my own. I remember a conversation I had with my mother-in-law and oldest daughter that began as reminiscing over a person who became a lost love to all of us. We all talked about different aspects of my wife but shortly, it transformed into a “who meant more to her” fest.

All our points of view were out of love, but each of us had a different angle for different reasons. My mother-in-law saw my wife’s death as the loss of her baby girl, my daughter, as the loss of her mother and me, as the loss of my love. The conversation became elevated because not only was it a sensitive topic, but it became a comparison.

I dubbed this the “Umbrella Effect” because it felt like an umbrella that fit three but caused each of us to become wet on one side. When my mother-in-law made a comment that got me thinking, I had to back off my somewhat defensive position. She talked about how she felt when my wife was born. It soon made me think about how my wife felt when our babies were born, and I realized that I was solely the contributor in each case. The connections that my mother-in-law and my daughter had trumped my 18 years automatically. These two ladies had true connections with my wife. Love based on biology beats loves based on time and experiences, any day.

We all had a relevant case, but mine was getting weaker with every statement made. I had to understand that biological connections give a different justification for reminiscing. As a husband, I was torn between defending my love for my wife and understanding my mother-in-law and my daughter’s points of view. Although it hurt, I had to realize the source of the pain. I no longer wanted to be an unconscious contributor to their hurt. I had to realize that everybody mourns loss differently, and comparing only brought more hurt to an already sensitive situation.

To alleviate the tension, I grabbed three bowls from my mother-in-law’s cupboard, got the scooper, and three spoons. I pulled out the cookie dough ice cream, which prompted a truce. Peace is always achievable over ice cream. I now know that although people can be subjected to the same grief, they all process and see it differently. What is good is that everybody remembers her for the beauty she brought to our family. Although our conversation got contentious at times, it was clear that although we lost her, no one lost the love we have for her.

Grief Literacy and Developmental Disability

By Carrie Batt, Grief Educator

Grief literacy has become a popular topic, yet it is a topic that is untapped within the disability community, specifically within the developmental sector. The sector supports and empowers people with a developmental disability and consists of families, their loved ones and service providers.

Within the sector there are very few conversations, education, or shared expertise about grief, loss, and disability. The pandemic brought to light the sheer lack of education and support that exists about grief, loss, and disability. My way of dealing with such a realization was to try to make a small change, which began by forwarding a proposal to my employer, requesting that we offer grief literacy sessions. The proposal was accepted, and we successfully offered four 1-hour grief literacy sessions, which reached a total of 20 participants. What we learned in offering these sessions was the value of learning new language to help in expressing and describing their grief experiences as, often, people with a developmental disability have grief stories that so often are unacknowledged and go unnoticed. Their grief histories are often extensive, and very painful. The painful history of the grief experienced amongst people with a developmental disability that begins with the atrocities of the institutions, the Huronia Regional Centre, The Ontario Hospital School, and The Orillia Asylum. The magnitude of such grief and loss has only recently been made public.

There is such an enormous amount of grief and the loss that until recently was unnoticed. Such unacknowledged grief within the developmental sector is far more common than ever imagined, especially when we include that of our direct support workers. Currently their grief is unheard of. Consider for a moment, supporting someone for ten years in their home, and when the supported person dies, cleaning out their room to prepare it for the next person to move in, and doing so without any recognition of your personal grief. Such scenarios play out daily within our developmental sector and just being expected to carry on with the work is the norm.

With that said, the reality remains that the developmental services sector can only benefit from receiving support and guidance from the bereavement support services sector. Such a partnership would help to bridge the gaps and begin dedicating resources towards, training education, and understanding about grief, loss and disability.

Birthdays, Anniversaries, and Other Special Days

Rachel Herrington – Social Service Worker Graduate, Third Year Psychology Student, Equal Rights and Community Advocate

It has been 10 years since my grandmother passed away and it never fails, every year leading up to her birthday I spend weeks with a pit of sadness and remorse in my stomach. I spend my days feeling this way and not understanding why then something makes the date catch my eye and it hits – It’s her birthday.

When we are grieving, some days are more difficult than others. Grief comes in waves like the sea and can feel like an intertwining labyrinth of emotions. Birthdays, anniversaries, and special dates that are associated with our loved one who has died can contribute to more emotionally intense days which can be worsened through the anticipation and “what ifs” of the upcoming day. These difficult days can leave us feeling defeated and it can almost feel like we’ve taken two steps backward in our grieving process, but grief does not have a timeline, and these feelings of setbacks are opportunities for healing.

Before the Day:

Communicate and set boundaries with others – think about how you want to approach the day and share your wants, needs, and desires with others. Clearly communicating your wants and needs with others will allow the opportunity for you to set the expectation for the day which can help relieve the intense feelings of anticipation.

Remember there is no right or wrong way to celebrate special days – It is important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve and there is no written code or rule on how these special days are to be approached. However you decide to approach the day is the right way.

On the Day:

Allow yourself the opportunity for space from others – it is important to allow there to be an opportunity for you to step away and have a safe space to feel your emotions if you need to. If you are attending someone else’s home for the occasion plan a way that you can step away or leave with ease if you need to.

Find something that grounds you when intense emotions arise – if intense emotions are arising it can be helpful to find something to help ground you in the moment. This could be a physical item such as a small trinket in your pocket that you can hold, squeeze, and focus on in your hand, or it can be through positive mental imagery, deep breathing, and/or stress relieving acupressure, etc.

Take deep breaths – practicing deep breathing can help reduce stress and can increase resiliency during highly emotional or stressful situations.

If things don’t go as planned, that is okay – grief is a process with no timelines or set of rules, and sometimes things do not always go the way we plan and that is okay. Allow yourself time, patience, and understanding while you adapt to living with your unique grief experience.

When Death Feels like a Thief

By Amanda Sebastian-Carrier.

Amanda Sebastian-Carrier is a communications professional who writes about her grief journey as a form of healing.

Thief!

Oh, how loudly I’d yell the words, shaking my fist at its back as it ran from me through the crowded bazaar. You would find me, soaked in tears, panting and crying and trying to explain that something very precious had been taken from me by that, that, THAT THIEF!

In the heart of my grief, at my frailest, all I could see was what was no more. I grieved all that was stolen from me by death; love, security and even my very self. Had I known the value of having every pocket of who I was, picked bare by grief, I would not have fought so hard to hold onto it all. I’d have let that cutpurse have it all without raising an alarm. That egg, it could take the golden globs of joy, the silvery wisps of laughter and the precious stones of delight that once filled my world and sell them all to the highest bidder. How could I have seen the faceless bidder, behind their paddle, was me. Grief, that panderer, was only taking from me what I could not currently carry and would sell it back, piece by piece, as the currency of healing was paid.

If only I’d had a clue that the larceny committed by grief was not the crime I was reporting, I’d have stopped much earlier. Before death, I had no idea that the theft of all you knew and love and the process of reclaiming your sense of security and self were a process that had the ability to change your life forever, but not how you might think. Grief and mourning can lead to healing if you do the work. If you don’t waste time filing reports to the universe about the misappropriation of your loved one. If you immerse yourself in the process of mourning, instead of decrying the looting of your life. If you truly, honestly, and mindfully, say goodbye instead of trying to hold on. If you can do all that, the only thing that grief is able to steal is your pain. You just have to be willing to give it up, let it be taken.

It’s only now, after I have made my peace with the plundering pirates of grief that I can see what I saw as theft, was actually a gift. The thief that is grief was not stealing all that was happy and good in my life, it was stealing my pain. Grief sat on me, taking all the things I didn’t know how to process, and filtered them through different lenses. It sat with me, taking from me each tear that fell, each shaky breath and each battered heartbeat. Grief took all I had, each story, each memory, and each emotion from me until I began to have room to process life again. Grief took, not a life in the way death had, but death; out of the way of life. Death stole life and grief; grief gave it back.

Tending to My Garden of Grief

By Taylor Bourassa, RP & Professional Art Therapist.

Losing a loved one –whether through death or the end of a relationship, brings up complex emotions, some of which are hard to process. The first major loss I can remember experiencing was when I was quite young and my grandfather died. I barely knew the man, but to this day we still share stories of his impact on my father, his son, my mother, his daughter-in-law, and us, his grandchildren. The memories bubble up slowly and play in my mind like a distorted movie playing on the television screen. It is part of my life I can’t quite recollect without the input of others. Then in my middle teen years I attended a funeral for my grandmother’s sister, and I remember watching the grief flood my grandmother’s face as she dissolved into tears and I wondered: how can I, or any one else hold this grief in the “right” way? How can any of us help ease that pain?

When I was 16 or 17, my cat, who I still recognize as my earliest best friend, developed cancer and needed to be put down. This was the hardest thing I had had to face at that point in my young life. I was faced with what seemed to be inconsolable grief. That same thought bubbled up: how can anyone ease this unbearable pain?

A few years ago I was faced again with the reality of our mortality on this planet Earth when my dog, Roxy, had to be put down due to ailing health and decline. That same question flitted through my mind. Now, at 29, and having faced multiple losses and deaths I finally have some semblance of an answer to that question. It isn’t straightforward, and it probably isn’t universal. But it feels appropriate for me: remember, honour and celebrate. The pain of these losses will more than likely be with me my entire life, until the day I die and pass the pain onto my loved ones left behind. So long as I remember the lives of those I have lost, honour their presence and impact on me and celebrate their spirit, they will continue to live with me and the pain will feel bearable. It will no longer stop me in my tracks. Instead, it will encourage me and propel me forward through the transmutation of that grief into something different, something more nuanced and fluid. I’d like to share a practice for processing grief which I have found to be especially helpful.

Reflect on person or pet that has passed on and write a letter to them. Use recycled, bio-degradable paper to write this letter, so that when you get to the end of this invitation and you plant your letter it will be taken back into the earth and soil.

Imagine the things you appreciate about this person, the memories you two share, the impact they have had on you, and anything you feel has been left unsaid or unexpressed while they were still living. Before you close and seal the letter, read it back to yourself and sit with whatever memories, feelings and thoughts come up. Allow the energy of this person to show up and sit with that felt sense of who they were. When you are ready, fill the envelope with your letter and the seeds of your choice: flowers, fruits or vegetables. Use the seeds which you feel best honours the person. Find a location that is both accessible to you and reflects a space of honouring and celebration. This may be a favourite shared space between the two of you, or a new spot you would like to crop out as a way to honour and remember them. Once you have found your spot, take your letter and your seeds and bury them in this spot. Eventually, the seeds you have planted will sprout and grow, changing the spot into a new gravesite garden. Soon, the biodegradable letter will also be gone, subsumed back into the womb of the earth and soil, feeding the land for the growth and propagation of the flowers you have planted. Maybe these flowers will remain only in the space you created, or, what is more likely, they will be spread on the wind and the legs of bees, and the beaks of birds until the grass beneath is forever changed, peppered with new and continuing growth.

What a beautiful way to honour the deceased: recognizing their continued impact on you and the world around you as they and their memory connects with and returns to the earth. I find this to be a helpful way to process my own grief because it allows me an embodied, tangible and somatic way of addressing, honouring and processing the grief held inside my body. The grief will always be there in some capacity, and now there is a space which I can visit and reflect. The heaviness and weight of the grief is no longer mine alone – the whole earth helps me to carry it. Grief is such a unique, yet universal experience. My own experiencing of grief is all I know for certain, and so I keep searching for answers. I hope that as you navigate your own grief, you can alleviate some of the weight by sharing the load with the natural world around you.

What I know about grief

Post by Alyssa Warmland, artist, activist, well-practiced griever.

I earned my “grief card” at 15, when I lost my mother. Since then, I’ve experienced other instances of loss and have become a well-practiced griever. Most recently, I lost a friend in a tragic way. She was deeply connected within our rural Ontario community and as I grieve her loss, I’m watching many other people around me grieve. Some, like me, are experienced in grief. Others are newer to the experience.

The following are some things I know to be true about grief for me, based on my lived experience. Some of them may resonate with you as well. Grief is unique to the people experiencing it in each moment, so please take whatever makes sense to you from this share and leave whatever doesn’t.

– Give yourself space to just feel the waves. Sometimes it feels like it’s not quite so intense, and then sometimes it feels like you’ve just been punched in the stomach. And it’ll cycle around. And it won’t feel this way forever.

– You’re totally allowed to feel whatever it is you’re feeling. Last night, while I spoke with sobbing friends on the phone, I was absolutely furious. Today, it’s that gut-punch feeling. it’ll cycle around. And it won’t be this way forever.

– Sharing stories can be helpful. Celebrate the reasons you loved whoever you’re grieving. Look at the pictures. Watch the videos. Sing the songs.

– Be patient with yourself, but keep going through the motions of what you know you need to do to maintain your wellness while you grieve. Eat something, even if you’re not hungry. Sleep or lay down, even if you feel like you’ll never fall asleep (podcasts can help make it less overwhelming). Drink water. Go for a walk outside. Write about it. Work, if you want to work (and plan for some extensions on stuff if you can, so you can work a bit more slowly than usual if you need to)

– Your brain may take a little longer to process things. Your memory may not work as well. You may feel irritable or overwhelmed. It’s okay.

– If the death part itself was hard, try to avoid focusing on the end, and instead think about the person you loved and who they were when they were well.

– Connect with other people who are grieving, it may be easier to know you’re not alone.

To learn more about collective grief, please read Maureen’s post on the topic.

When Death Comes Suddenly

Some types of death we prepare for. If we have an elderly person in our life, one who has lived a good, long life and may be experiencing some health challenges that typically come with old age, then we may well be thinking about the possibility they will die. This type of death fits into the ‘natural order’ of life, and even if we don’t want it, we tend to accept that it is inevitable.

Similarly, we can prepare for death by illness or a chronic, deteriorating condition. We know this is happening and we have time to take action to give ourselves and the dying person some sense of completion as their time comes to an end.

Sudden, unexpected death is quite different. It’s really quite impossible to prepare for, and tends to leave us with a very different experience of grief. It’s important to note that sudden and unexpected death can happen in either of the above scenarios, too. An elderly person may be quite healthy, and die from an injury or sudden onset of a fatal condition. A person diagnosed with a terminal illness may die abruptly from complications or from a sudden event unrelated to their condition.

When someone dies suddenly we often struggle with grief that is raw, unpredictable and powerful. Some elements make it harder to cope, including:

The death feels out of the ‘natural order’ of life. Children are not supposed to die. Young people are not supposed to die. Sometimes, one partner is not expected to die before the other. It can make it hard to adapt when we feel that death is not “supposed to” happen at this time.

We have no chance to say goodbye or have a sense of conclusion to the relationship. We may have thought we had plenty of time to heal old wounds, to make up for neglect or take care of business with the person who died. It can be difficult to accept these missed opportunities, and they can bring a sense of guilt and regret.

The death may be violent, potentially painful and causing significant physical trauma. We can be left with terrible images. Whether we see the damage to our loved one or not, the human mind has a great capacity to imagine, and we can review the circumstances and the harm over and over again in our grieving mind.

We may worry that our loved one did not experience dignity in the circumstances of their death. We feel that the death is completely out of our control, and we may feel like we failed our loved one in some way due to their experience or the circumstances.

When someone you love has died suddenly and unexpectedly, it may feel quite different than any other type of loss you have experienced. Try to keep these factors in mind, and be gentle with yourself as you adapt to this sudden change in your life and adjust to their absence.