Posts Tagged ‘Loss’

Preparing For and Coping with Special Days

Special Days can be days we have honoured with our loved ones that many others celebrate or more personal dates and milestones with your loved one. As these days approach, it can be difficult to figure out how to move through a Special Day. Do you do what you’ve always done? What do you do if you just want to ignore the day? Special Days can bring up a lot of different emotions, triggers, and opportunities to honour the person who has died.

Why Can Special Days Feel so Hard?

While we are grieving, it can feel as if our world has stopped while the rest of the world seems so happy and carry on as if nothing has happened. After the death of a loved one, there are other transitions and losses we can be grieving while we grieve the death. We may be letting go of old roles while taking on new roles in our family. There may be changes in our relationships and dynamics with others.

Planning Ahead Can Help Us Prepare

There’s no “right” way to feel as a Special Day approaches. You may dread the event, feel on edge, be angry at the number of store displays triggering your grief, or find yourself honouring your loved one and feeling joy.

Planning can help lower anxiety and can help us feel more prepared to cope. Grief can change from moment to moment. If your plans need to change the day of, that’s okay too.

Involve your support network that you usually spend this time with, including children, in conversations about what they would like to do. Everyone is impacted by grief, no matter their age, ability, gender, race, or other identities. You can find more information on grief and supporting grievers with intellectual disabilities here and a post about supporting grieving children here.

Taking Care of Yourselves Through and After Special Days

You may find that your grief is heavier in the lead-up to the Special Day, on the Special Day itself, or that you may experience a wave of grief in the day(s) afterwards.

Here are some gentle reminders:

- You may not be able to do all the things you have done or had planned to do, but be compassionate with yourself. You are allowed to set boundaries around your capacity so you can give yourself plenty of care and rest during this time.

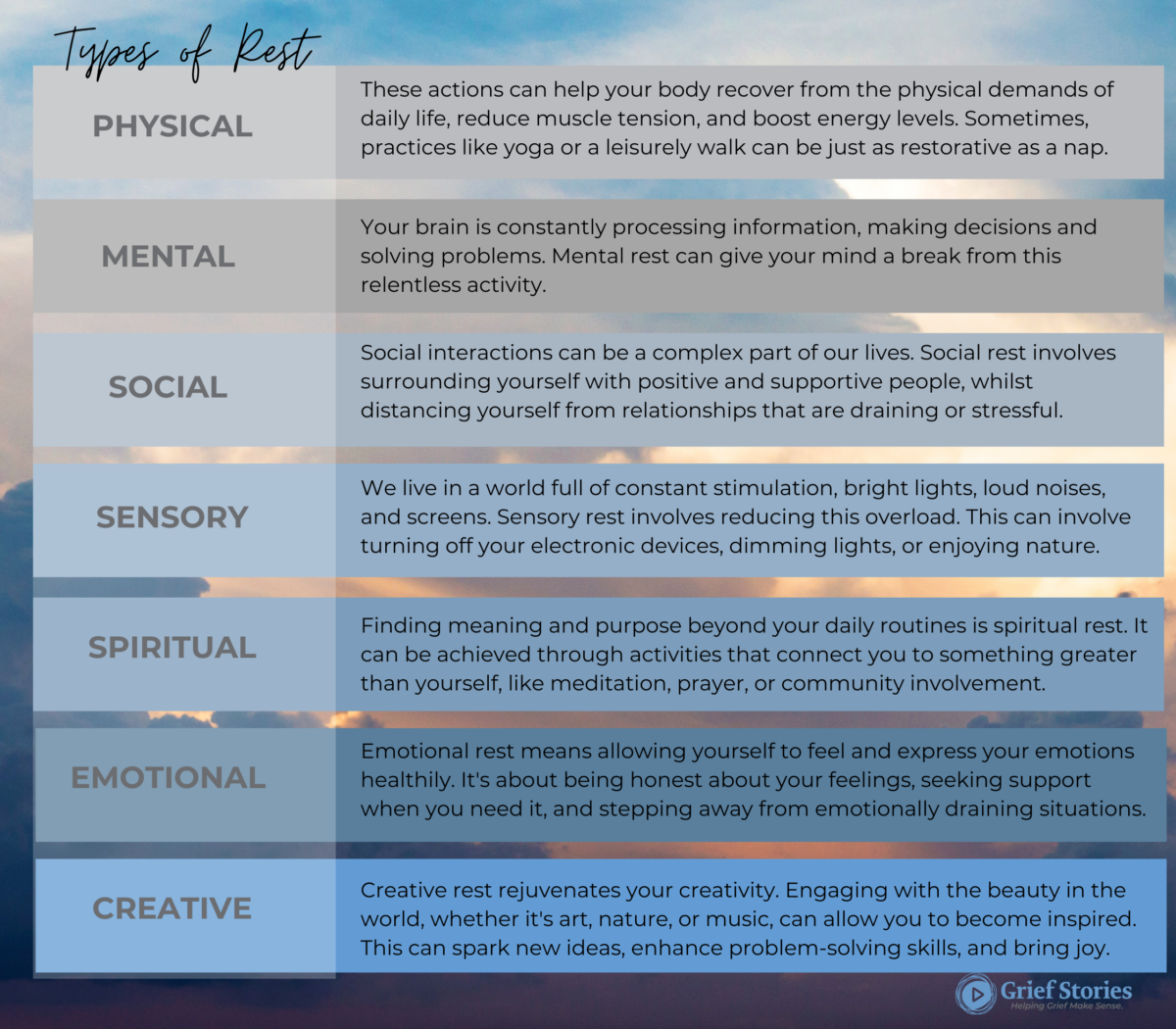

- Grief can impact us mentally, emotionally, and physically. We can find ourselves exhausted in different ways, especially after going through heavy days. Check out our tips on the different ways we can give ourselves rest and care as we grieve here.

- This time of year can have us grievers feeling more overwhelmed or lonely at this time of year. If it feels right, think about it and reach out to people in your network you find supportive. Asking for specific support helps our loved ones give us what we need. The 3 H’s can help us name what type of support we may be needing:

- Heard: To feel listened to, validated, without judgement

- Help: Problem-solving, practical support like cooking, cleaning, childcare, etc.

- Hug: Sometimes we don’t need words of comfort, but a comforting touch like a hug.

- There is no right way to feel on a Special Day. You are allowed to experience moments of joy and lightness on these days while also missing your loved one.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW. Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Finding Joy During the Holidays After Loss When Everything Feels Awful: A message of hope.

My mother died in the middle of the night on January 1, four days before I turned sixteen. I don’t remember much about Christmas the couple weeks before she died, just that we spent a lot of that season in the ICU of the hospital where my mother had birthed my brother and I. For a decade after she died, I hated Christmas. Everything filled me with dread and heaviness. The lights, decorations, and music made my skin crawl- and they were inescapable. At the grocery store, at work, looking out my apartment window onto the main street of a small town. The traditions my family had grown up with weren’t things we did anymore. The holidays weren’t joyful, connective, or fun.

Now, I am thirty-three and the mother of two little humans. I have officially crossed the threshold of being alive longer without my mother than with her. My motherhood has come with many gifts and one of them has been finding joy during the holidays again. I’m writing this cozied in a bright red snoopy sweater that says “merry”. My partner and brother have matching ones. My older kid told me he wants to decorate our house with rainbow-coloured lights, so I bought a strand to hang on the weekend and a small wreath with red berries that reminded me of my mother. I hung the wreath on my front door and thought about how she probably would have hung the lights with my son the same day he had the idea if she were alive.

Last month, my cousin got married and had set up a table of pictures of family members who had died so they could be part of the big day. My beautiful mother was there, smiling brightly out of the frame. My kid noticed it, we have the same picture of her on our fridge. “It’s your mama! She died. We could bring her back and visit her at her house,” said my sweet four-year old. I remind him that death doesn’t work that way, but she lives in our hearts. The next day, he brought her up again and I told him a story about her. It doesn’t feel heavy, even though I still miss her. I feel grateful to feel her presence in our lives. Grief, though still present, changes over time.

If you are someone who is grieving during the holidays and can relate to the first part of my story, I want you to know that it might not feel that way forever. I also want you to know it’s okay to feel however you’re feeling- there are no rules in grief. Here are a few things I’ve learned about grief and the holidays:

Sometimes it can help to make new traditions.

When my older kid was old enough to enjoy Christmas for the first time, I asked my partner, my brother, and other family members if they had any traditions they wanted to start incorporating into the season. We’re still working on building these traditions with my kids, but things like Christmas Eve dinner with my aunt and uncle, Christmas morning with my dad, not wrapping Santa gifts, baking cookies, and hanging rainbow-coloured lights are all slowly becoming ways to find joy, intentionally, together.

- Don’t overextend yourself.

If you don’t want to participate in every (or any) holiday activity- don’t! I didn’t decorate for years, I still avoid malls between November 15-January 1, and there have been some years where I intentionally scheduled work things so I didn’t have to participate at all. It’s okay to be gentle with yourself when it comes to participating in holiday-related things while you’re grieving.

3. Giving can be healing.

I do a lot of my planned giving to charity during the holiday season. I use affiliate programs connected to a breastfeeding support organization I’m passionate about to buy gifts for family and friends, I make donations to organizations that are important to loved ones in their names, and I give to grief resources and hospices as I can. Knowing I am helping other people during a season that has traditionally been hard for me helps me feel connected and supports my continuous healing.

If you find support through the resources we create at Grief Stories, please consider helping us reach our fundraising goal this holiday season so we can continue to produce and distribute free grief resources. Giving is grief support. You can donate here.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Alyssa Warmland is an interdisciplinary artist and activist. Her work utilizes elements of radical vulnerability, restorative justice, mindfulness, compassion, performance, and direct action.

She is a mother, La Leche League Leader, Board member of La Leche League Canada, writer, podcaster, producer, director, performer, content creator, not-for-profit administrator, and abstract visual artist. Lyss is a strong advocate for fumbling towards an ethic of care, especially when it comes to the topics of birth, matresence, and grief. Most of all, she’s interested in the way people choose to tell their stories and how that keeps them well.

Infant & Reproductive Loss Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDFs for Individuals and Professionals]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. Mental health professionals designed this toolkit for individuals, parents, caregivers, and families navigating perinatal and reproductive loss.

Reactions to pregnancy and reproductive loss are as unique as fingerprints. Some can process the experience relatively quickly, while others experience unrelenting pain and grief.

We hope that this toolkit can be used to add tools to your toolbox and offer words of support, guidance, and care as you navigate life after loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Individuals HERE.

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit was designed by mental health professionals for other professionals who support individuals during their reproductive years and beyond.

It contains information about grief and navigating the impact of loss alongside your clients.High-quality grief care includes compassionate and open communication, informed choice and individualized care. Compassionate communication, the most important element, is required in all aspects of care throughout and following loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Supporting Professionals HERE.

Always Kiss Me Goodnight : Deborah Dickson

Deborah Dickson recently released a book about grief for children called Always Kiss Me Goodnight. She recently reached out to us at Grief Stories to share a bit about it and the accompanying guidebook for parents and teachers who support kids in grief and we are honoured to share a bit more about this important resource.

Deborah’s mother, Wanda Marie McLaughlin, passed away at age 39 on November 8th, 1974 when Deborah was 19 years old. Her search for understanding and “figuring out what was missing” in her life, turned on an awareness switch. There was more behind this awareness than she realized.

Grief Stories: Tell us a little more about your experience writing Always Kiss Me Goodnight.

Deborah: “Always Kiss Me Goodnight” is based on my true story of heartbreak stemming from the loss of my mom when I was a young adult. I felt responsible for my three brothers, helped with household chores, and worked full time all while trying to navigate my grieving journey.

Writing this book was amazing, tearful, and filled with learning. It was gratifying to be able to share my personal story with children alongside the wonderful digital illustrations by our grandson Ronan to correlate with the story. Keeping the storyline simple but real and informative from my perspective was an amazing learning and therapeutic journey. I am forever grateful for the writing opportunity and for the strength I learned from my Mom. I cherish our family memories. It furthers my belief in being kind and helping others.

I wrote this book about grieving to help others (and myself) acknowledge and understand the challenging and painful emotions one has following the loss of a loved one. I emphasize the importance of asking questions, the never-ending search for answers, and not being afraid to ask for help – these were the pieces I learned from my own journey.”

Grief Stories: Based on your personal experience, what recommendations do you have for parents who are supporting children in grief ?

Deborah: “‘Family’ to me is ‘everything’.

Tragedy can cause so much grief and sadness that family members may fail to recognize each other’s emotions and needs – especially children’s. While it is important to try to be strong, it is also important for children to see a parent’s sadness and tears. Age-appropriate communication is also important, children need to be included in planning and have an understanding of what is going on. It’s important to provide a safe environment for the children to talk about the loss, even if it’s not with you.

People can support children by allowing them to express whatever emotion they are feeling without judgment. If the family is beyond knowing what to do for themselves or their children – reach out for professional help. Don’t continue to be afraid or alone, it is healthier for all to reach out.”

Grief Stories: As is relates to the parent/teacher guide you created to go alongside your book, what are the key tips for supporting children.

Deborah:

- Parents may want to protect their children from painful grief emotions by hiding their emotions. However, it is important that parents take time to recognize, acknowledge, and express their grief in healthy ways. This lets parents honour their own grief needs, while also modeling healthy coping behaviours for their children.

- Communication is vital, reassure them that you or someone else is always available to come to.

- Focus on reassurance, family memories, recall vacations and pictures. Encourage them to draw, make a scrap book, or a collage.

- If you don’t have an answer for them know that that is okay – you ask for help – reach out to professionals and don’t feel that you are all alone dealing with the grieving process.

- Talk to them, hug them, tell that they are loved, that they are heard and they are safe.

Losing my Mom at an early age has impacted my life in so many ways. I wanted to share my story and other resources to help parents and children, should they face a tragedy like the loss of a loved one. I hope that this book can be of some service and an avenue to explore difficult conversations. May you enjoy “Always Kiss Me Goodnight” and hug your family tight and often.

You can find out more about Deborah and “ Always Kiss Me Goodnight “ through her website https://www.neversaygoodbye.ca/home.

Who are we to Decide? The Many Paths through Grief

A lot of my work with clients involves hearing their stories, but also answering many questions about if their grief is “normal”. Their grief is overwhelming, and our dominant culture’s strong message is – that grief should be kept at its edges, I often find this pervasive intention creeps into griever’s experiences – and my worldview at times. I even catch myself apologizing for crying in public spaces, shutting down my process. There are many ways of doing, being, and knowing, which I continue to learn through the spaces I hold with others.

A Ghanaian woman living in Canada shared with me her experiences after the death of her mother who died in their home country of Ghana. Traditionally, when someone dies in their community, their body is laid in the home and the entire community is welcomed. Feasts, songs, stories, cries, wails. Their world stops – and for longer than a mere few hours. Loud, open expressions of grief are honoured and welcomed.

A Chinese woman expressed worry that something was wrong with them. After attending a grief support group, she felt worse rather than better. So many people have shared how helpful these spaces had been for them, but this wasn’t her experience at all.

A White man sits across from me and tells me his wife encouraged him to try therapy because “he isn’t grieving” since he doesn’t openly share his emotions. One finds comfort in storytelling, talking about the loss of their child, and finds crying cathartic. He speaks about the qualities and memories of their child, practical matters over emotional ones, and their passion for bringing forth advocacy and change concerning the drug poisoning epidemic.

An Indigenous woman speaks about a ritual in their community where the grieving family cuts their hair after a loved one’s death. On one hand, they feel guilt at times for not engaging with it because it “makes it real”. However, getting a tattoo of a flower they got after their mother’s death was their ritual.

In North America, we are quick to try to “fix” or “solve” grief. There are many books, support groups, and online communities about grief. Yet I have had more than a handful of clients who have recently experienced a death share how their doctor offered them a psychopharmacological medication before their doctor may even acknowledge their loss. I think about the Ghanaian woman, and how open and welcome grief is within their local community. I can only imagine how stifling tending to these rituals in North America may have felt to this person if their mother died in Canada.

There is no “magic pill” to prescribe, but I know many people in the depths of their grief wish there were something, anything to “fast forward” through the sleepless nights, waves of emotion, and grief bursts to a place where their grief feels less overwhelming. There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

Here are some gentle prompts for you to explore some ways to tend to your grief:

What brings meaning or comfort, to you?

Are there particular rituals your community (spiritual, ethnic, other identities) find important to help honour your loved one?

Which rituals do you find comforting but at times find it difficult to share with others?

Just because White colonizer culture is dominant in North America, does not mean those perspectives are “the right way” through grief and loss. There are many ways of being, doing and knowing in life and in grief.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Holding Space for The Many Faces of Grief on Father’s Day

A lot of blog posts and articles about grief and special days tend to focus on how to navigate these moments when our loved one has died. Often these articles of grief also talk about the ways we have deeply loved or cared for the person who has died.

Grief is a natural response to when we lose someone or something we have had a connection to. So what happens for the grievers who have had a not-so-loving relationship with the person who has died, or has experienced an estrangement?

I’ve heard folx sitting across from me talk about how surprising it was to experience a surge of emotions after finding out their father died after being estranged for half their life. Another person talked about how frustrating it was to hear others ask them why it didn’t seem they were grieving, and that they “should” be more tearful because their father had died, however, these people did not know how difficult their relationship with and to their father was when he was alive. Someone else shares how hard it is to carry the grief of deciding to estrange themselves from their father.

To those of you grieving and/or approaching this Father’s Day with complex feelings and memories of a not-so-loving relationship: you are not alone. We grieve because we have had a connection – and a connection can be filled with many things. Love may be part of these connections in our life, but so many other complex emotions, and situations can be part of these connections. People are complicated. Love is complicated. Grief is also complicated.

We can grieve that we did not have the relationship with the person we needed, grieve the parts of the person we miss, or even grieve for a future where perhaps we may have been able to repair the rupture in our relationship.

Grief can feel even more complicated when we have a complex relationship with the person we are grieving. It can make us feel even more isolated. Disenfranchised Grief is any type of grief where society has denied the griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. When a relationship has been not-so-loving we may hear well-intentioned people telling us ‘You shouldn’t feel grief because X was not a good person or not a big part of your life’. Our society also tends to prioritize grief experiences through death, and not non-death losses like an estrangement from a parent.

Whether your father has died and you had a complex relationship with them, are grieving the living relationship with your father you never were able to have, or grieving an estrangement from your Father your feelings are valid. Grief is not just one emotion, but is a natural response that can have many different emotions depending on the person. It’s okay if you feel anger, frustration, regret, guilt, and even relief. Special days where all we hear and see are advertisements talking about Father’s Day can bring up extra waves of grief as we near this date.

Here are some gentle reminders if you are moving through Father’s Day this year and have a complicated relationship with your father, or paternal figure in your life:

- Give yourself permission to write a letter to this person, expressing the things you never have been able to say. It can be a place to put down all those thoughts and feelings that you can then release. Feel free to rip this letter up into a tiny pieces, flush it down the toilet, or even safely burn the page.

- Spend time that day however you need to and with people who support you.

- Our biological family is just one connection we have, but we also create our own “chosen family” of close relationships. You may feel compelled to send a card or write a note to someone you feel creates a paternal presence in your life like a good friend, mentor, or another relative.

- Allow yourself rest as you move through the day as grief can be an exhausting experience on our minds and bodies.

Maybe you’ve lost your father or father figure to death, or you’ve lost your father figuratively because of dementia, or you’ve lost your father in your life because of his unacceptance of your lifestyle. In whatever case, you’re not alone.

However you navigate this day, know this:

- If you feel happy, that is okay

- If you feel sad, that is okay

- If you feel angry, that is okay

- If you feel a roller coaster of emotions, that is okay

- If you feel nothing, that is okay

- If you don’t WANT to feel anything today, that is okay

The reality is that no one can tell you how to feel about your situation.

Your feelings are valid. However you choose to be, honour that, honour you.

Grief, Exhaustion, & Rest

Many people consider grief to be a response to the death of a loved one, but we grieve so much more than that. Grief is an emotional response to loss of any kind. Both real or perceived loss can trigger the response. The loss of a job, a miscarriage, a breakup, losing a sentimental item, or big life changes like moving can all cause grief.

Grief fatigue is a very real thing. Even though we know that grief is a healthy response to loss, it’s perfectly normal to get tired of it. You’re not in intense pain, but it also isn’t getting any easier yet. It’s exhausting. Grief exhaustion refers to the deep and pervasive fatigue often accompanying the grieving process. It goes beyond the typical tiredness we experience in our daily lives and stems from the immense emotional and psychological strain that grief places upon us.

Grief can leave you feeling drained, both physically and mentally, making even the simplest tasks seem overwhelming. Even typical activities can feel like too much when our physical body and brain refuses to cooperate. The mind and body are closely connected and the grief process is a good example of that. The mental and emotional toll of grief can wreak havoc on a person’s mental and physical well-being.

Emotions are not always easy to deal with and having intense ones can be incredibly draining. Grief is a complex emotion that can be mentally and physically taxing. The profound sadness and range of emotions experienced during the different stages of grief can lead to fatigue and exhaustion. Even though you’re tired, you may have trouble sleeping or sleep a lot and never feel rested.

We often blame grief exhaustion on sleep deprivation—and that is a component. Sleep is essential, and needs to be prioritized. But, so many of us still feel exhausted and burnt out even when we finally start sleeping. Grief exhaustion isn’t solved with more sleep. Dr. Saundra Dalton Smith says we need seven types of rest. As I read her work, I find it especially applicable to grief.

Dr. Saundra pointed out that taking a comprehensive approach to rest is a bridge to better sleep and this is handled with attentive self-care. When we talk about rest outside of sleep, our minds might immediately jump to stereotypical “self-care” activities, like getting a massage or taking a bubble bath. Real self-care is nurturing our current needs. We might need to rest mentally, or to reconnect with our friends, or to be vulnerable with our emotions. Our needs are often rooted in the types of rest and what we’re lacking.

Being able to pinpoint what you and your body need in terms of rest will allow you to address the area and choose a restful activity that fits your needs.

When we understand the types of rest, we can become better aware of our own needs and make small changes in our lives that leave us feeling more whole, more energized, and more refreshed.

Grief Busting Zine [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. We’re sorry you’re feeling this way right now but so glad you’re reading this.

This zine is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

Physical copies of this sine were originally distributed at Cultivate Festival in 2023.

Community Grief Toolkit [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in the community. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and how to build the resources for further support.

What Can Help with Early Traumatic Grief?

By Claire Irwin

When your child dies you are thrown into a nightmare. None of this is expected to be easy.

Even after several months, it still isn’t. There have been some things that have helped us during

our grief. Maybe they will help you, too.

1. Let someone organize a meal train. The community rallied, making sure we had meals

delivered to our home for weeks after our daughter died. I have zero idea what we would have

done without this. Right after this traumatic loss I couldn’t even think about eating, let alone

cooking and meal planning.

2. Grief counselling. Our counsellor comes every week since the second day. Some may not agree, but honestly, we have learned some great survival tools and have our feelings validated.

To be able to talk about it all in a safe environment is very helpful, and just talking about

everything helps.

3. Find something to keep you busy. Mind you, we haven’t found our way to any gym yet or back to work, but we find other ways to move our bodies. Gardening, cutting grass, walks,

landscaping, anything really to get our bodies moving has really helped us.

4. Try journaling. I wish I started this earlier. If you can find it in you to do it, I recommend it. For me personally, it helps get whatever is in my head out on paper. I document how I’m feeling. I also get my anger out on paper too. I’ve been learning that you can let it build up inside of you. This energy needs to get out. I find writing very helpful for me. I journal daily. Plus, it helps me keep my days in order because they tend to blend.

5. Let your support system hold you. This has been a huge help. I don’t know where I would be today if I didn’t have the people closest to us. Lean into them and let them help. Use them as sounding boards. Whatever it is you need, if they are willing and able to be there for you, let

them. It’s not easy asking for help or accepting it, but it’s helped us feel loved and seen. It’s also

helped us back on our feet a bit.

At the core of it all, just remembering to breathe is sometimes all you can do. Something our

grief counsellor has taught us right from the very beginning:

Inhale 4 seconds…Hold 7 seconds…Exhale 8 seconds. Repeat as needed.

Like I said, surviving this grief and trauma isn’t easy, and it doesn’t come with a handbook. We

are all just doing the best we can, and it’s sucks all at the same time. Our loss cannot be fixed, it

can only be carried, and these are some of the things helping us to carry it now.

Shadowloss: loss in life

By Alyssa Warmland

Shadowloss is a term developed by Cole Imperi, a thanatologist and the founder of The American School of Thanatology. It describes the types of loss we feel in life, rather than the loss of life. Shadowlosses are things like divorce or the end of a long-term relationship, infertility, a medical diagnosis, losing a job, or the loss of some other relationship or thing. It’s a loss that impacts the life of an individual, as well as their social network in their life.

Sometimes, the loss of a being coexists with shadowloss. For example, when a loved one dies, families are often tasked with sorting through the person (or animal)’s belongings. When my dog died, I remember packing her bowls, her toys, her leash, and her collars away in a box I made space for in my crowded apartment because I couldn’t stand the loss of throwing them out. I remember holding her favourite toys and feeling deeply in grief. The “big loss” was my beloved dog, but the shadowloss was when I got rid of some of her belongings and how hard that piece was. It felt like a tug in the pit of my stomach when I turned towards the wall where her water dish used to sit, only to see an empty bit of wall.

Another example of shadowloss in my life was when I was fired from a job at a women’s shelter. I’d thought, all through my undergrad, that I would work in one. I worked hard to get my gender studies degree and to volunteer with feminist organizations that targeted violence against women. And, after applying four or five times, I finally got the job. I loved it, although the rest of the staff was far more conservative than I am and I sensed that I was not a great fit, in spite of my knowledge and my passion for the work. I was fired, just before the end of my probation, and refused an explanation as to exactly why. I was devastated. Not only was I losing a job, I felt as though I was losing a dream and a sense of self. Years, and a whole career, later, I still experience huge waves of grief related to that loss.

What we know about types of loss is that we experience grief related to them in very similar ways. Waves of sadness, anger, and the sense that something/someone is missing are a few things that can come up with “big loss” and with shadowloss. As with any type of grief, it’s not particularly useful to rank and compare types of loss or experiences of grief. But having language to describe the experience of grief associated with the loss of a thing or part of someone/their life can be useful. This allows us to acknowledge those losses as ones where we leave ourselves some space to grieve. It can also be another opportunity to connect in this life where there are shared human experiences like the complex plurality that is grief.

The Meaning of Tisha B’Av

By Richard Quodomine

Starting on sundown, July 26th, some Jews will begin to fast. Unlike the more well-known Yom Kippur, which is for atonement, Tisha B’Av is a specific holiday for mourning and grief. Its exact date varies with the ancient Jewish lunar Calendar, but is sometime in July or early August. All Jewish commemorations begin in the evening due to this lunar calendar.

Observant Jews will abstain from sexual relations, all forms of frivolity, wearing of leather, and work on this day. Just before the evening that begins the holiday, a “separation meal,” called seudah hamafseket,is eaten.It consists of bread and a hard-boiled egg dipped in ashes, accompanied by water. Talk about a meal to remind one of sadness. Once the evening of Tisha B’Av commences, one fasts for a full 24 hours. Please note that life and health are more important than fasting in Jewish tradition. If a doctor says a person should not fast, such as a woman who is pregnant, then fasting is forbidden.

Those of us of the Jewish faith also ascribe several sad events as having happened on the day of Tisha B’Av. For example, it is traditionally believed that both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem were destroyed on Tisha B’Av. In more recent history, the last Jews of Spain whom did not convert to Catholicism were said to have left Spain forever on Tisha B’Av. Spanish Judaism had been a critical component of the Islamic culture there and was part of its unique pluralism and beauty. Some of those events may not have happened “on that day” exactly. The point of the holiday is not to take dates literally, but rather to remind ourselves that grief is a life cycle event, and we all grieve at some time.

Further, there is grief over loss of life but also grief for losing ways of living, of culture, of beauty or perhaps our environment and our friends who are not well treated by society. Tisha B’Av is a Jewish holiday, but it is also a holiday that is universal. No, we shouldn’t all fast or refuse to wear leather. But we should recognize that mourning is important. Feeling loss and grief is a part of whom we are. In facing that loss and accepting that grief – along with emotions such as anger, sadness or resentment – we are able to process them. We’re able to find a part of ourselves. For example, when dealing with a person who has passed, the grief we bear is knowing that we must carry that which we have lost because the person who carried them with us can no longer do it. We must grieve, and then bring about again the joy that that person created. The prayer for the holiday concludes with the verse “Restore us to You, O Lord, that we may be restored! Renew our days as of old.” In accepting grief, we can be restored to joy.