Posts Tagged ‘Healing’

A Million Other Things: Grieving a Drug Poisoning Death

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

A parent sits across from me, anxiously wringing their hands. They will be returning to work after the sudden death of their child. “What if they ask? Do I tell them that they died of an overdose?” Terror flashes across their face. “What if they judge me? My child? What if they think I’m a terrible parent?” We take a moment to reflect on their child and I ask them to tell me about them. They pause, but then I notice their hands aren’t as tense as they cross them over their shoulders. “They were so thoughtful and gave the best hugs. Their smile would light up any room.”

Sister, father, son, niece, best friend – some of these words might be how you would describe your loved one who has died of an overdose or drug poisoning. People Who Use Drugs (PWUD) are not defined by their substance use – they are a million other things to those who love and miss them dearly. Drug poisoning and overdose deaths are stigmatized in our society. The focus is on how the person died, not who they are. Society still holds onto old notions and beliefs about drugs which come with a value judgment about people who use drugs, which further contributes to stigma. Not everyone who uses drugs is an addict and not all drug use is inherently problematic. People who use drugs deserve dignity and respect when we are remembering and honouring those who have died by overdose or drug poisoning.

More stigma means less support for people using drugs and those that support them. Much work has been done and continues to be done to dispel myths and stigma about addiction, drug use, and those who use drugs. Addiction is an illness: something that someone lives with, not something that defines them. These same values and judgments society has about drug use aren’t attached to folks who die of other illnesses. Society tends to view drug use and those who use them as a black and white issue. However, those who love someone who uses drugs weave a rich, colourful tapestry made of stories, reminders, and feelings about their loved one.

In my years as a grief therapist, those left behind want to share a special moment or memory about their loved one with a trusted other. When one is grieving a drug-poisoning death, this trust and sacredness without judgment offers the freedom to sit in the entirety of their grief—the grief they felt when their loved one was alive and when they died. Taking the time to use a loved one’s name in conversation, and asking the griever to share something about their loved one is a powerful tool for us on our grief journey. By initiating these types of conversations, we let the griever know that if they wish to, they can talk about their loved one. Sharing our stories are some of the most powerful ways one finds connection and healing through grief. It helps us feel less alone in our grief by sharing about what makes our person special. Those we love and grieve aren’t just a person who uses drugs – they are so much more. May each of us continue to share stories about our loved ones and the many facets their lives hold.

*DISCLAIMER* The scenario described in the article is a general reflection upon themes the author has witnessed through their grief counselling work and does not represent a specific individual in order to protect the confidentiality of service users.

Nicole – Using Art and Creativity to Express Grief

Nicole – Using Art and Creativity to Express Grief

Nicole discusses the work she does to allow access to creative outlets such as art hives and gardening.

Alongside

By Mike Bonikowsky

Grief is the great leveller, and the great divider. Everyone grieves, sooner or later, but no two people will experience it in the same way. No two bereavements are the same, and neither are any two consolations.

This is only more poignantly the case for people with developmental disabilities. Not only is their grief completely unique, but they are often unable to express it in traditional ways. How are we to support someone through the grieving process when they cannot, or will not, tell us what they are thinking and feeling about their loss? The answer is simple, and difficult.

In Christian theology, there is a concept called “the Holy Spirit”. This is the invisible piece of God that is everywhere all the time, with and within all people. The name given to this in the original ancient Greek is the “Paraclete”, literally, “The one who comes alongside.”

That is also our best, and only role, when supporting a person with a developmental disability to grieve. We must be the one that comes alongside. There is no closer place we can get to. We must be present, be with, perhaps not understanding or comprehending what the person we support is experiencing, but alongside them nonetheless. We must be there, ready to provide whatever we can discover of their unique need in grief.

But that coming alongside must begin before the bereavement. We must already have been there through the happier seasons of the person’s life, if we are to know them well enough to read the language of their grieving, and hope to know in what little ways we may support them. Supporting a person with a developmental disability to grieve is not a matter of coming alongside, but of remaining where we already were. It is a matter of knowing and being known by them, of being trusted. It is not so much a matter of doing anything for the person, but of being something for them: A safe place, a consistent and reliable presence. It is to be a fixed point in a confusing, chaotic world, someone of whom they can say: “When that person is here, I can expect things to be like this.” Only when this relationship is present and well-established in the ordinary times can we come alongside in the darkest, loneliest season on the person’s life, and hope to meet their unspoken needs.

And usually the answer to those needs is what it has always been: To simply be there with them, to prepare a meal for them and do the dishes afterward, to help them wash body and find clean clothes to wear. To open the curtains in the morning, so that when they emerge from the dark cave of their unique grief, for however short a time, they are greeted by a world that has not ended, and a face that they know, and that knows them.

Grief & Ice Cream

By John (Lewis) Clark, Author of upcoming book (Cook Away Your Grief).

When my wife of 18 years died in 2016, I became a single father missing the love of my life, and also had to learn how to raise two girls (13-17 at the time) on my own. I remember a conversation I had with my mother-in-law and oldest daughter that began as reminiscing over a person who became a lost love to all of us. We all talked about different aspects of my wife but shortly, it transformed into a “who meant more to her” fest.

All our points of view were out of love, but each of us had a different angle for different reasons. My mother-in-law saw my wife’s death as the loss of her baby girl, my daughter, as the loss of her mother and me, as the loss of my love. The conversation became elevated because not only was it a sensitive topic, but it became a comparison.

I dubbed this the “Umbrella Effect” because it felt like an umbrella that fit three but caused each of us to become wet on one side. When my mother-in-law made a comment that got me thinking, I had to back off my somewhat defensive position. She talked about how she felt when my wife was born. It soon made me think about how my wife felt when our babies were born, and I realized that I was solely the contributor in each case. The connections that my mother-in-law and my daughter had trumped my 18 years automatically. These two ladies had true connections with my wife. Love based on biology beats loves based on time and experiences, any day.

We all had a relevant case, but mine was getting weaker with every statement made. I had to understand that biological connections give a different justification for reminiscing. As a husband, I was torn between defending my love for my wife and understanding my mother-in-law and my daughter’s points of view. Although it hurt, I had to realize the source of the pain. I no longer wanted to be an unconscious contributor to their hurt. I had to realize that everybody mourns loss differently, and comparing only brought more hurt to an already sensitive situation.

To alleviate the tension, I grabbed three bowls from my mother-in-law’s cupboard, got the scooper, and three spoons. I pulled out the cookie dough ice cream, which prompted a truce. Peace is always achievable over ice cream. I now know that although people can be subjected to the same grief, they all process and see it differently. What is good is that everybody remembers her for the beauty she brought to our family. Although our conversation got contentious at times, it was clear that although we lost her, no one lost the love we have for her.

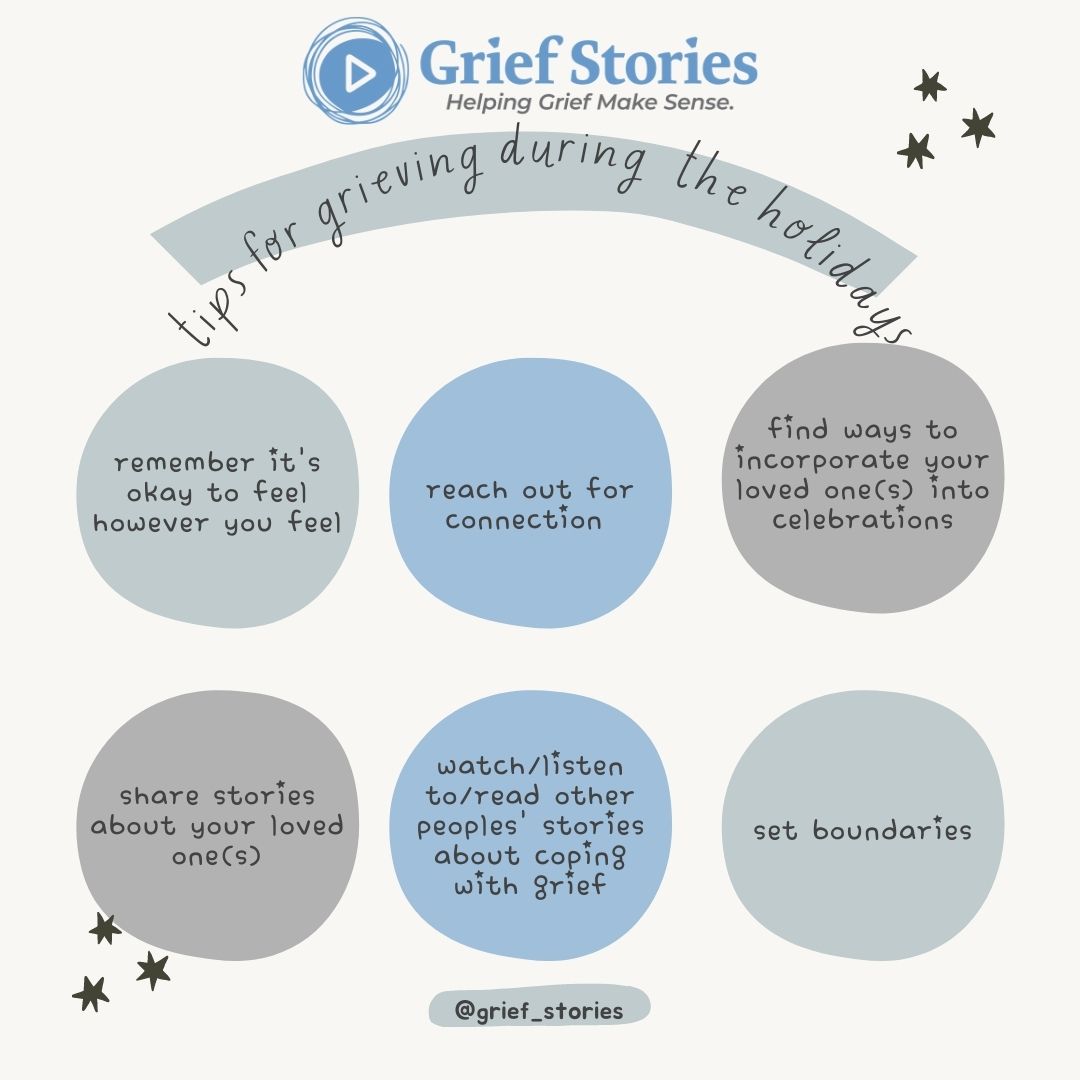

Tips for Grieving During the Holidays

By Alyssa Warmland

The holidays can bring up a lot of feelings, especially when you’re grieving the loss of a loved one. Whether it’s the first holiday season without someone, the holidays mark a time where someone you love died, or it’s just hard to be around celebration when you’re not feeling celebratory, December can feel heavy.

These are a few tips for grieving during the holidays:

Remind yourself that it’s okay to feel however you feel.

Feeling sad or mad? Feeling happy- and guilty for not feeling worse? Whatever comes up for you is normal. It’s okay to sit with your feelings, to give them some space when it feels right, and also to compartmentalize them if you feel like that’s best in the moment. You can acknowledge your feelings, put them in your pocket, and hold on to them during the family dinner if you want to. You can take them out of your pocket and spend time with them later. Grief is unique, and can show up in unexpected ways. It’s okay to feel however you feel.

Reach out for connection.

Sometimes we worry that we’ll make someone else upset if we mention our grief, or if we show up in a way that isn’t particularly festive. The truth is, the people who care about us want to hold space for us, even when we’re grieving. Connection can help us feel better.

Find ways to incorporate your loved one(s) into celebrations.

Did your dad have a favourite side dish your family always served at dinner? Did Oma make sugar cookies every year? Did your sister always compliment you when you wore red? Consider serving dad’s dish, or baking Oma’s cookies, or wearing red.

Share stories about your loved ones.

Sometimes it can be tempting to pretend the people we love haven’t died. As if, by not talking about them, we can pretend they’re still around. In fact, sharing stories about them can help honour them and to feel their presence. Remembering our loved ones out loud in connection with other people can feel healing.

Watch/listen/read other peoples’ stories and insights about grief.

At griefstories.org , we host stories and insights from people with lived experience in grief, as well as healthcare professionals’ insights on grief. These videos, podcasts, and blog posts are available for free 24/7, anywhere you can access the internet. Our hope is that this content may help you feel less alone.

Set boundaries.

Listen to how your body feels. You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do. You are safe and you are worthy of operating with integrity toward yourself. Grief can be hard, and it’s okay to be gentle with yourself as you move in and through it – even during the holidays. Set whatever boundaries feel right for you. There are no rules here. You’ve got this.

Learning from Grief

By Noelle Bailey

Grief is weird. Odd start, I know, but that was the sentence I used a lot whenever someone asked me how I was. It was never a constant feeling; it changed day to day. And still does. It’s the full gambit of emotions from sadness to anger to guilt and, though dark, even humour found its way in.

In December of 2019, I lost my father. His health had been declining for several months, and we had started the process to diagnose and begin treatment for what we knew was probably cancer. At his first appointment with his oncologist, he was immediately admitted to the ER. By the next day he was on a ventilator, and within twelve days they came to tell me that the cancer had spread everywhere. We had lost a fight we hadn’t even really begun. In March of 2022, my mother passed away after a 14 year fight with MS. It was a much different process to lose her by degrees over those 14 years, witnessing her own body turn against her while powerless to do anything to stop it.

Those are my two experiences with the strangeness of grief. They were vastly different experiences, but also similar in that they cut me in two and changed my life.

The two biggest things I’ve taken from my grieving process are these:

1. I will, for the rest of my life, miss the conversations we will never have. There are books I’ve read since they left that I would love to talk to my mom about. My dad never got to hear about my new job, and he would have loved it. Pictures people have brought me that I can never ask them about, stories I missed out on hearing. The moments of my life, big and small, that they won’t be here for is the part that takes me under every time.

2. I can grieve however I need to. It doesn’t need to look a certain way or be anything other than what I need. I struggled a lot after losing my mom with the idea that I wasn’t sad enough or broken enough because after watching her long hard battle there was a certain peace lacing itself through the pain. When we laid my parents to rest in the cemetery next to my grandparents, we played “The Rainbow Connection” sung by Kermit the Frog because that’s what my mom had always said she wanted to play to say goodbye. Then my husband, Cale, and I did a shot of Jack, like my dad and Cale did when they went out for my dad’s 60th.

I’ve never been very good at setting boundaries in my life, but I tried very hard to make sure I set them surrounding my grief. To let myself do whatever I needed to process the loss of my parents and not to let anyone tell me I should be acting or feeling a certain way. I laughed at things they would have laughed at, and when I needed to, I cried. I am slowly learning how to live in a world without my parents, and know that I will be for the rest of my life.

There One Day and Gone the Next : Art Therapy and Grief

By Sarah Smith DTATI, BFA

Over the last 12 years or so, I’ve had the opportunity to work with those grieving individually and in group settings, which has provided me with experience and insight into how art therapy (and art as therapy) can be beneficial to those dealing with loss.

What is Art Therapy?

“Art therapy combines the creative process and psychotherapy, facilitating self-exploration and understanding. Using imagery, colour and shape as part of this creative therapeutic process, thoughts and feelings can be expressed that would otherwise be difficult to articulate,”(CATA, 2022).

There’s no right or wrong in art therapy, it’s a matter of using the art as a vessel for wellness along side a trained professional. There are many benefits one can receive from engaging in the art making process such as: healthy coping strategies, insight, emotional stability/balance, stress /anxiety reduction, grounding of emotions, pleasure/joy, creativity, safe space, expression, control, freedom, and connection among many others!

Art Therapy and Grief

Grief is a very layered and challenging thing that is unique for each individual who experiences loss.

Because there is no “proper” way to grieve, art therapy can make for an excellent coping strategy as it allows for each person to express themselves in the way that’s best for them.

Unlike traditional “talk therapy”, art therapy has the art, so this means that one does not need to speak if they don’t want to or if they cant find the way to articulate how they feel into words. Sometimes, while people are grieving they cant even pin point how they feel and at other times the emotions can just be so overwhelming it can affect one physically and to try and talk about the emotions just exacerbates them.

Creating art in itself can be a healing thing. It can be a fun or relaxing thing to do. Engaging in an art therapy session can allow for so many more benefits. The art therapist can provide the participant with specific art therapy directives and art materials that they feel may be beneficial to your needs. Art therapists are trained to read and assess clients’ artwork. This means they may see things you may have missed that you might benefit from if brought to your attention. This insight makes it a great learning tool for self-discovery. We as art therapists believe that the art work holds the subconscious. What’s great about this for those who are grieving is that people can process however they need to. Some people need more time to process, some people need a more gentle approach where they feel in control, some people refuse to acknowledge things, and some people are just going through the motions and engaging in the art making process. The subconscious is purging and the healing is happening whether they realize it or not.

Art Therapy Directives (examples)

I facilitated a workshop at a hospice a couple years ago and offered it to those who had lost a loved one. The workshop began with a few art therapy warm-up exercises with the intention of helping everyone feel a bit more comfortable in the space and with each other.

The first art therapy directive I had them do was make flowers out of coffee filters, markers, and water. I wanted them to make something symbolic for their loved one. They began by writing whatever they wanted onto the coffee filters. Some people wrote the persons name, poems, a memory, or even drew a picture. They then watered down the filters and the colours began to bleed. Some people cried during this part. They could resonate with the symbolism. The water like tears. The bleeding of the colours representing pain, fuzzy memories, and a distant grasp on the person. When the coffee filters had dried we had turned them into flowers. The transformation of taking what we lost and carrying it forward in a new way was very powerful to witness and a very healing thing to say the least.

The second art therapy directive was focused more on the individual rather than the deceased. I gave everyone a mask. I instructed them to paint the front of the mask how they appear to the world and I asked them to create on the inside of the mask to show how they really feel or how they are actually doing (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

They shared their art work from the workshop, but it was heavy. They were feeling sensitive and tired among other feelings so I had them sit and talk for a bit and then had them pull a self-care card for a distraction before letting them and drive home, as it may not have otherwise been safe for anyone overwhelmed after such an engaging session. This is typically how I run a grief workshop. Before they left the hospice asked them to fill out a score sheet to see how they felt about participating in the workshop and everyone said they liked it and for reasons, such as that they felt less anxious, they felt less alone, the felt lighter and more hopeful after the workshop.

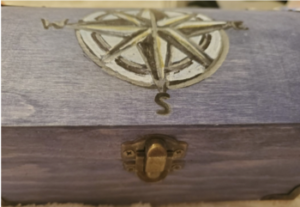

At another hospice art therapy workshop, I had them create memory boxes. I provided them with a wooden box along with a variety of art materials, the only thing I asked was that they brought in a picture of the person they had lost. The purpose of this was to give them an opportunity to create something that could hold two energies, a place to honour them deceased, but also something tangible for them to have and hold. From my observations, I remember them taking a lot of time on these boxes and they were very quiet while making them. When they shared them, they were emotional, of course, but pride came through, it was like they made them for their people and wanted to make them well, so that their loved one would really like the box. This made them feel good for reasons such as honouring the person still while they are gone. Some people felt that their guilt had been eased a bit because they were physically doing something for that person who was no longer here. To see an example, see figure 2 and 2b.

Figure 2

Figure 2b.

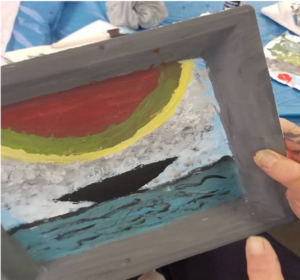

Following the memory boxes, I had them paint a step by step painting for their loved one. This was more of an art as therapy approach. This means they were literally using the art itself for wellness. They followed along with me and painted a whole painting. By following me, they were able to safely let go and get lost in the art making process. The intention was to enjoy the process while also giving them a healthy mental and emotional escape for however long it took us to paint the picture. I selected a picture of trees that had no leaves, purposely to symbolize letting go, loss, and reflection but the painting had an element of hope to it, the tress were pointing up to the sky, facing the light and there was lots of colour (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

The photos below are some examples of art from some of my sessions with clients around grief. They speak for themselves.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Grief Literacy and Developmental Disability

By Carrie Batt, Grief Educator

Grief literacy has become a popular topic, yet it is a topic that is untapped within the disability community, specifically within the developmental sector. The sector supports and empowers people with a developmental disability and consists of families, their loved ones and service providers.

Within the sector there are very few conversations, education, or shared expertise about grief, loss, and disability. The pandemic brought to light the sheer lack of education and support that exists about grief, loss, and disability. My way of dealing with such a realization was to try to make a small change, which began by forwarding a proposal to my employer, requesting that we offer grief literacy sessions. The proposal was accepted, and we successfully offered four 1-hour grief literacy sessions, which reached a total of 20 participants. What we learned in offering these sessions was the value of learning new language to help in expressing and describing their grief experiences as, often, people with a developmental disability have grief stories that so often are unacknowledged and go unnoticed. Their grief histories are often extensive, and very painful. The painful history of the grief experienced amongst people with a developmental disability that begins with the atrocities of the institutions, the Huronia Regional Centre, The Ontario Hospital School, and The Orillia Asylum. The magnitude of such grief and loss has only recently been made public.

There is such an enormous amount of grief and the loss that until recently was unnoticed. Such unacknowledged grief within the developmental sector is far more common than ever imagined, especially when we include that of our direct support workers. Currently their grief is unheard of. Consider for a moment, supporting someone for ten years in their home, and when the supported person dies, cleaning out their room to prepare it for the next person to move in, and doing so without any recognition of your personal grief. Such scenarios play out daily within our developmental sector and just being expected to carry on with the work is the norm.

With that said, the reality remains that the developmental services sector can only benefit from receiving support and guidance from the bereavement support services sector. Such a partnership would help to bridge the gaps and begin dedicating resources towards, training education, and understanding about grief, loss and disability.

When Death Feels like a Thief

By Amanda Sebastian-Carrier.

Amanda Sebastian-Carrier is a communications professional who writes about her grief journey as a form of healing.

Thief!

Oh, how loudly I’d yell the words, shaking my fist at its back as it ran from me through the crowded bazaar. You would find me, soaked in tears, panting and crying and trying to explain that something very precious had been taken from me by that, that, THAT THIEF!

In the heart of my grief, at my frailest, all I could see was what was no more. I grieved all that was stolen from me by death; love, security and even my very self. Had I known the value of having every pocket of who I was, picked bare by grief, I would not have fought so hard to hold onto it all. I’d have let that cutpurse have it all without raising an alarm. That egg, it could take the golden globs of joy, the silvery wisps of laughter and the precious stones of delight that once filled my world and sell them all to the highest bidder. How could I have seen the faceless bidder, behind their paddle, was me. Grief, that panderer, was only taking from me what I could not currently carry and would sell it back, piece by piece, as the currency of healing was paid.

If only I’d had a clue that the larceny committed by grief was not the crime I was reporting, I’d have stopped much earlier. Before death, I had no idea that the theft of all you knew and love and the process of reclaiming your sense of security and self were a process that had the ability to change your life forever, but not how you might think. Grief and mourning can lead to healing if you do the work. If you don’t waste time filing reports to the universe about the misappropriation of your loved one. If you immerse yourself in the process of mourning, instead of decrying the looting of your life. If you truly, honestly, and mindfully, say goodbye instead of trying to hold on. If you can do all that, the only thing that grief is able to steal is your pain. You just have to be willing to give it up, let it be taken.

It’s only now, after I have made my peace with the plundering pirates of grief that I can see what I saw as theft, was actually a gift. The thief that is grief was not stealing all that was happy and good in my life, it was stealing my pain. Grief sat on me, taking all the things I didn’t know how to process, and filtered them through different lenses. It sat with me, taking from me each tear that fell, each shaky breath and each battered heartbeat. Grief took all I had, each story, each memory, and each emotion from me until I began to have room to process life again. Grief took, not a life in the way death had, but death; out of the way of life. Death stole life and grief; grief gave it back.

What Does Grief Support Look Like?

Post by Maureen Pollard, MSW, RSW

When we experience significant, on-going symptoms of grief that interfere with our adjustment to the reality of our loss, it can be time to seek professional help. It can be difficult to know where to find help and what grief support options are available.

Begin by asking for a referral. Maybe your family or friends have received good grief support they would recommend. Your doctor can typically provide a referral or you can conduct an internet search. When you find a grief support program on the internet, take time to examine the website thoroughly then connect by email or telephone to ask any questions you have before deciding which support might be the best fit for you.

Types of Grief Support:

Individual counselling with a therapist. A professional who has experience and knowledge in the area of dying, death and grief will listen to your story without judgment and then co-create a plan for healing that feels comfortable for you. The time you spend in counselling should be dedicated to your grief, with a focus on helping you find your way through your experience using information, insights and skill of the therapist to help you through the complex feelings and tasks.

Group therapy. This type of support may be led by a professional, or may be offered by peers who have experienced a similar loss. Groups can offer a rich support experience that lets you know you are not alone, and offers you the opportunity to learn from several others living with a similar loss. The time you spend in group will be shared and with a focus on topics relevant to the group’s purpose rather than any one group member’s situation. It’s important to learn about how the group works and what types of activities you’ll experience as you decide whether to try attending a group. If the group is run by peers, ask what type of training and support they received to ensure they’re delivering quality care.

On-line forums. There are many groups and forums focused on grief education and support on the internet. These are easy to access and allow you to participate at your own comfort level, either by simply reading posts or actively sharing your own situation, seeking support and offering support to others. A forum can create a sense of community among its membership, providing a great source of information and support from others who have a similar experience of loss who share what they have learned. In public internet forums there is always a risk of interference by people who post to cause trouble, but private, members-only, moderated forums can significantly reduce this risk.

Remember, whatever type of grief support you try beyond family and friends, don’t be afraid to quit if the style or structure of the support doesn’t feel comfortable or helpful. If you’re still experiencing the symptoms that led to your decision to seek additional help, please don’t stop trying to find the kind of support that can meet your needs. There are many different types of counsellors, groups and forums and it can take some time to find the one that’s right for you. Your healing is worth it!

What I know about grief

Post by Alyssa Warmland, artist, activist, well-practiced griever.

I earned my “grief card” at 15, when I lost my mother. Since then, I’ve experienced other instances of loss and have become a well-practiced griever. Most recently, I lost a friend in a tragic way. She was deeply connected within our rural Ontario community and as I grieve her loss, I’m watching many other people around me grieve. Some, like me, are experienced in grief. Others are newer to the experience.

The following are some things I know to be true about grief for me, based on my lived experience. Some of them may resonate with you as well. Grief is unique to the people experiencing it in each moment, so please take whatever makes sense to you from this share and leave whatever doesn’t.

– Give yourself space to just feel the waves. Sometimes it feels like it’s not quite so intense, and then sometimes it feels like you’ve just been punched in the stomach. And it’ll cycle around. And it won’t feel this way forever.

– You’re totally allowed to feel whatever it is you’re feeling. Last night, while I spoke with sobbing friends on the phone, I was absolutely furious. Today, it’s that gut-punch feeling. it’ll cycle around. And it won’t be this way forever.

– Sharing stories can be helpful. Celebrate the reasons you loved whoever you’re grieving. Look at the pictures. Watch the videos. Sing the songs.

– Be patient with yourself, but keep going through the motions of what you know you need to do to maintain your wellness while you grieve. Eat something, even if you’re not hungry. Sleep or lay down, even if you feel like you’ll never fall asleep (podcasts can help make it less overwhelming). Drink water. Go for a walk outside. Write about it. Work, if you want to work (and plan for some extensions on stuff if you can, so you can work a bit more slowly than usual if you need to)

– Your brain may take a little longer to process things. Your memory may not work as well. You may feel irritable or overwhelmed. It’s okay.

– If the death part itself was hard, try to avoid focusing on the end, and instead think about the person you loved and who they were when they were well.

– Connect with other people who are grieving, it may be easier to know you’re not alone.

To learn more about collective grief, please read Maureen’s post on the topic.

Jane – Grief and meditation

Jane – Grief and meditation

Jane shares how she practices daily meditation and how that helps her manage her thoughts and feelings.