Posts Tagged ‘grieving’

Preparing For and Coping with Special Days

Special Days can be days we have honoured with our loved ones that many others celebrate or more personal dates and milestones with your loved one. As these days approach, it can be difficult to figure out how to move through a Special Day. Do you do what you’ve always done? What do you do if you just want to ignore the day? Special Days can bring up a lot of different emotions, triggers, and opportunities to honour the person who has died.

Why Can Special Days Feel so Hard?

While we are grieving, it can feel as if our world has stopped while the rest of the world seems so happy and carry on as if nothing has happened. After the death of a loved one, there are other transitions and losses we can be grieving while we grieve the death. We may be letting go of old roles while taking on new roles in our family. There may be changes in our relationships and dynamics with others.

Planning Ahead Can Help Us Prepare

There’s no “right” way to feel as a Special Day approaches. You may dread the event, feel on edge, be angry at the number of store displays triggering your grief, or find yourself honouring your loved one and feeling joy.

Planning can help lower anxiety and can help us feel more prepared to cope. Grief can change from moment to moment. If your plans need to change the day of, that’s okay too.

Involve your support network that you usually spend this time with, including children, in conversations about what they would like to do. Everyone is impacted by grief, no matter their age, ability, gender, race, or other identities. You can find more information on grief and supporting grievers with intellectual disabilities here and a post about supporting grieving children here.

Taking Care of Yourselves Through and After Special Days

You may find that your grief is heavier in the lead-up to the Special Day, on the Special Day itself, or that you may experience a wave of grief in the day(s) afterwards.

Here are some gentle reminders:

- You may not be able to do all the things you have done or had planned to do, but be compassionate with yourself. You are allowed to set boundaries around your capacity so you can give yourself plenty of care and rest during this time.

- Grief can impact us mentally, emotionally, and physically. We can find ourselves exhausted in different ways, especially after going through heavy days. Check out our tips on the different ways we can give ourselves rest and care as we grieve here.

- This time of year can have us grievers feeling more overwhelmed or lonely at this time of year. If it feels right, think about it and reach out to people in your network you find supportive. Asking for specific support helps our loved ones give us what we need. The 3 H’s can help us name what type of support we may be needing:

- Heard: To feel listened to, validated, without judgement

- Help: Problem-solving, practical support like cooking, cleaning, childcare, etc.

- Hug: Sometimes we don’t need words of comfort, but a comforting touch like a hug.

- There is no right way to feel on a Special Day. You are allowed to experience moments of joy and lightness on these days while also missing your loved one.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW. Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Finding Joy During the Holidays After Loss When Everything Feels Awful: A message of hope.

My mother died in the middle of the night on January 1, four days before I turned sixteen. I don’t remember much about Christmas the couple weeks before she died, just that we spent a lot of that season in the ICU of the hospital where my mother had birthed my brother and I. For a decade after she died, I hated Christmas. Everything filled me with dread and heaviness. The lights, decorations, and music made my skin crawl- and they were inescapable. At the grocery store, at work, looking out my apartment window onto the main street of a small town. The traditions my family had grown up with weren’t things we did anymore. The holidays weren’t joyful, connective, or fun.

Now, I am thirty-three and the mother of two little humans. I have officially crossed the threshold of being alive longer without my mother than with her. My motherhood has come with many gifts and one of them has been finding joy during the holidays again. I’m writing this cozied in a bright red snoopy sweater that says “merry”. My partner and brother have matching ones. My older kid told me he wants to decorate our house with rainbow-coloured lights, so I bought a strand to hang on the weekend and a small wreath with red berries that reminded me of my mother. I hung the wreath on my front door and thought about how she probably would have hung the lights with my son the same day he had the idea if she were alive.

Last month, my cousin got married and had set up a table of pictures of family members who had died so they could be part of the big day. My beautiful mother was there, smiling brightly out of the frame. My kid noticed it, we have the same picture of her on our fridge. “It’s your mama! She died. We could bring her back and visit her at her house,” said my sweet four-year old. I remind him that death doesn’t work that way, but she lives in our hearts. The next day, he brought her up again and I told him a story about her. It doesn’t feel heavy, even though I still miss her. I feel grateful to feel her presence in our lives. Grief, though still present, changes over time.

If you are someone who is grieving during the holidays and can relate to the first part of my story, I want you to know that it might not feel that way forever. I also want you to know it’s okay to feel however you’re feeling- there are no rules in grief. Here are a few things I’ve learned about grief and the holidays:

Sometimes it can help to make new traditions.

When my older kid was old enough to enjoy Christmas for the first time, I asked my partner, my brother, and other family members if they had any traditions they wanted to start incorporating into the season. We’re still working on building these traditions with my kids, but things like Christmas Eve dinner with my aunt and uncle, Christmas morning with my dad, not wrapping Santa gifts, baking cookies, and hanging rainbow-coloured lights are all slowly becoming ways to find joy, intentionally, together.

- Don’t overextend yourself.

If you don’t want to participate in every (or any) holiday activity- don’t! I didn’t decorate for years, I still avoid malls between November 15-January 1, and there have been some years where I intentionally scheduled work things so I didn’t have to participate at all. It’s okay to be gentle with yourself when it comes to participating in holiday-related things while you’re grieving.

3. Giving can be healing.

I do a lot of my planned giving to charity during the holiday season. I use affiliate programs connected to a breastfeeding support organization I’m passionate about to buy gifts for family and friends, I make donations to organizations that are important to loved ones in their names, and I give to grief resources and hospices as I can. Knowing I am helping other people during a season that has traditionally been hard for me helps me feel connected and supports my continuous healing.

If you find support through the resources we create at Grief Stories, please consider helping us reach our fundraising goal this holiday season so we can continue to produce and distribute free grief resources. Giving is grief support. You can donate here.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Alyssa Warmland is an interdisciplinary artist and activist. Her work utilizes elements of radical vulnerability, restorative justice, mindfulness, compassion, performance, and direct action.

She is a mother, La Leche League Leader, Board member of La Leche League Canada, writer, podcaster, producer, director, performer, content creator, not-for-profit administrator, and abstract visual artist. Lyss is a strong advocate for fumbling towards an ethic of care, especially when it comes to the topics of birth, matresence, and grief. Most of all, she’s interested in the way people choose to tell their stories and how that keeps them well.

Suicide Loss Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDF]

Approximately 4500 people in Canada die by suicide each year. That is approximately 12 people who die by suicide each day. In 2022, 49,476 Americans died by suicide. That’s 1 death every 11 minutes. On average, 5 people grieve for every death. That leaves over 250,000 people experiencing suicide-related grief and distress. Grief Stories has seen these impacts firsthand: suicide loss has been the most viewed topic on our Youtube channel all year. At Grief Stories, we passionately believe sharing stories and insights fosters connection, helping people cope with grief. Grief Stories is proud to announce the release of our latest toolkit titled: the Suicide Loss Toolkit.

Our suicide loss toolkit pulls together our original multi-media resources about grief into an easy-to-access format which provides helpful information about the grief experience, stories of suicide loss from survivors, and helpful strategies to move through grief. This toolkit has been curated by mental health professionals for other helpers, for individuals, and their networks as they navigate grief and loss together. They are free to download and use.

Toolkits are becoming increasingly popular as a knowledge translation strategy for disseminating health and wellness information, to build awareness, inform, and change public and healthcare provider behaviour. Toolkits communicate messages to improve health and wellness and in changing practice to diverse audiences, including healthcare practitioners, community and health organizations, and policymakers.

Practicing Self Compassion while Grieving

Grief is messy, confusing, enormously painful, and never seems to follow a linear path. This is when we need to take care of ourselves deeply, and yet, why is it that this is also when we beat ourselves up the most?

We are good at being compassionate toward others when they are grieving — something especially evident in social media. The outpouring of love, support, and acknowledgment of the loss is substantial and immediate, giving us the opportunity to virtually show up for every single bereaved friend we have ever come into contact with. On the other hand, we are quite unpracticed at giving ourselves that same kind of loving sustenance or self-compassion.

According to pioneer researcher Kristin Neff, at its heart, self-compassion is “treating yourself with the same type of kind, caring support and understanding that you would show to anyone you cared about.” In essence, you honor and accept your humanness by recognizing that you will encounter personal failings and that life is hard at times for everyone, even yourself. Cultivating self-compassion means that you accept that you are part of the human condition and that you are not perfect.

For whatever reason, people still seem to adhere to a notion that there is a correct way to grieve — contributing to the irrational belief that there is something wrong with them.

In addition to all of the grieving you have been doing, it is important to consider engaging in activities that feel replenishing, like recharging a battery. This way you have the energy to continue to grieve. It is perfectly fine if you want to stay home from work one day or decline an invitation. It would also be great if you feel up to going out and having fun. Give yourself permission to experience the good and the bad. This creates the opportunity to normalize the experience and contributes to increased self-compassion.

So How Can We Practice Self-compassion When We Are Grieving?

We can take moments to actively bear witness to our own suffering and fully accept it.

Notice your pain, acknowledge how it feels and that the world, as you have known it, has changed. Even if you can’t provide self-compassion, try to at least recognize that you need some support and care at this time.

We give ourselves permission to be imperfect.

There is no such thing as perfection. Things will not work out the way you want them to all the time and you may not respond in the way you had envisioned. So what if you mess up? Everyone around you has done it before and will do it again, so you are in good company.

We think about what we would say to a friend who has gone through a similar issue, and we say those same things to ourselves, even if we don’t quite believe it just yet.

Write down exactly what you would say to someone who came to you with your problems — and then read it out loud to yourself over and over until it starts to feel familiar.

We think about ourselves.

Putting ourselves first is by no means selfish. It is okay to decline an invitation or take a sick day at work when you are feeling down. It is also okay to practice self-care. This might include limiting self-judgment when we experience positive feelings such as joy. Sometimes people also say things to us that feel distressing, even when we know it comes from a place of compassion. Take care of yourself by letting them know how you feel and what you might need from them instead.

We realize that there is no “correct” way to grieve.

Everyone grieves differently. Sometimes we feel like talking, sometimes we don’t want to talk about our loss at all. Sometimes we think about it every day and other times, we can go minutes, hours, or days without thinking about it. Sometimes we just want to go out and have fun with our friends or family. Grief is complicated — just know that you are doing the best you can.

We notice when we are being overly harsh or critical of ourselves.

We sometimes feel that we need a critical voice to get motivated, that by beating ourselves up we will “do better” in some way. We also might beat ourselves up and focus on feelings of guilt because it feels easier than attending to our pain. Self-compassion is about being okay with who you are and how things are unfolding. Just notice when this is happening, and try to soften your response.

We take breaks from social media.

It might feel too much for us at times, especially during anniversaries or birthdays, and we may need to unfollow our loved ones on social media until we feel emotionally ready to go back to it.

We seek professional help when we need it.

Therapy is not a sign of weakness or that something is wrong with you. Sometimes, we just need a little extra support.

We cultivate hope.

A major tenet of self-compassion is recognizing that our suffering is part of the human condition. No matter how hard things are right now, you are not alone and will get through this.

We forgive ourselves for not doing any of the above.

Grief & Drug Poisoning Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDF]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in communities of people who use drugs and friends, family, and professionals who work with people who use drugs. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and to build the resources for further support.

Who are we to Decide? The Many Paths through Grief

A lot of my work with clients involves hearing their stories, but also answering many questions about if their grief is “normal”. Their grief is overwhelming, and our dominant culture’s strong message is – that grief should be kept at its edges, I often find this pervasive intention creeps into griever’s experiences – and my worldview at times. I even catch myself apologizing for crying in public spaces, shutting down my process. There are many ways of doing, being, and knowing, which I continue to learn through the spaces I hold with others.

A Ghanaian woman living in Canada shared with me her experiences after the death of her mother who died in their home country of Ghana. Traditionally, when someone dies in their community, their body is laid in the home and the entire community is welcomed. Feasts, songs, stories, cries, wails. Their world stops – and for longer than a mere few hours. Loud, open expressions of grief are honoured and welcomed.

A Chinese woman expressed worry that something was wrong with them. After attending a grief support group, she felt worse rather than better. So many people have shared how helpful these spaces had been for them, but this wasn’t her experience at all.

A White man sits across from me and tells me his wife encouraged him to try therapy because “he isn’t grieving” since he doesn’t openly share his emotions. One finds comfort in storytelling, talking about the loss of their child, and finds crying cathartic. He speaks about the qualities and memories of their child, practical matters over emotional ones, and their passion for bringing forth advocacy and change concerning the drug poisoning epidemic.

An Indigenous woman speaks about a ritual in their community where the grieving family cuts their hair after a loved one’s death. On one hand, they feel guilt at times for not engaging with it because it “makes it real”. However, getting a tattoo of a flower they got after their mother’s death was their ritual.

In North America, we are quick to try to “fix” or “solve” grief. There are many books, support groups, and online communities about grief. Yet I have had more than a handful of clients who have recently experienced a death share how their doctor offered them a psychopharmacological medication before their doctor may even acknowledge their loss. I think about the Ghanaian woman, and how open and welcome grief is within their local community. I can only imagine how stifling tending to these rituals in North America may have felt to this person if their mother died in Canada.

There is no “magic pill” to prescribe, but I know many people in the depths of their grief wish there were something, anything to “fast forward” through the sleepless nights, waves of emotion, and grief bursts to a place where their grief feels less overwhelming. There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

Here are some gentle prompts for you to explore some ways to tend to your grief:

What brings meaning or comfort, to you?

Are there particular rituals your community (spiritual, ethnic, other identities) find important to help honour your loved one?

Which rituals do you find comforting but at times find it difficult to share with others?

Just because White colonizer culture is dominant in North America, does not mean those perspectives are “the right way” through grief and loss. There are many ways of being, doing and knowing in life and in grief.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Creating Mother’s Day Traditions as a member of the Dead Mom Club

About a week after Easter this year, I noticed I was starting to feel off. My sleep wasn’t as restful, experiencing tension in my body, at times I was getting irritated with the simplest things. Then while streaming an episode of television, 4 ads back to back all talking about Mother’s Day. Then came the promotional emails, the store displays, and even a banner at the top of my Microsoft Word app directing users to their Mother’s Day templates.

Each year, my relationship with Mother’s Day has changed and it will likely continue to transform for the rest of my life. Early in my grief, I avoided any reminders. It was so difficult to work my part-time job in high school with Mother’s Day displays all around me, hearing about patrons’ plans, and then being asked how my own family would celebrate. I would feel my grief weigh heavily on my body, wanting to sleep until June 1st if I could. My first few Mother’s Days were about survival mode, and getting through my waves of grief.

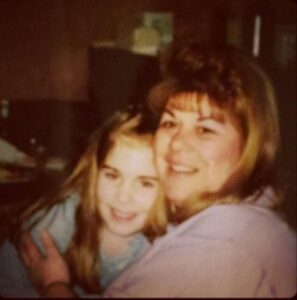

Photo of Jessica and her mother, facing the camera and smiling.

I’m not crushed by my Mother’s Day grief these days in the same way, but I know it is a time of year for me when my grief can show up more. Thoughts about what she would think about streaming platforms; the things I want to tell her; the things I want to thank her for. As my grief has changed these past 18 years, I’ve written letters to my mom, worn pieces of her jewelry, visited her gravesite, bought and written a Mother’s Day card she would have liked, and made some of my favourite childhood recipes of hers.

I would spend many of my Mother’s Days with my grandmother, my mom’s mom as I knew that day held its difficulties for her too. As my grandmother’s health declined over the pandemic, I wasn’t always able or allowed to visit with restrictions. After she died in 2021, I was in a fog by the time Mother’s Day 2022 came around. It felt surreal to me, that on my mother’s side – there are no longer any living maternal presences in my life.

Photo of Jessica wearing a blue satin dress and her mother wearing a long black and

white floral jacket , holding hands as if they are dancing for the camera.

Last year, a friend and another member of the Dead Mom Club were talking about how much this time of year can impact us. These conversations led to something surprising, and beautiful, but also a new tradition that I look forward to engaging in this year. Last Mother’s Day, we had dinner at a nice restaurant downtown, dressed up, and spent an evening talking about our moms. I wore a skirt that belonged to my grandmother and some jewelry that belonged to my mom. My friend also shared items they were wearing or keeping with them that reminded them of their mom. We laughed, we cried, we hugged. It was so cathartic to talk about the things some of our other friends couldn’t quite understand. At times dreading that 2nd Sunday in May, I now know that I can hold space for the difficult emotions that may arise and that I can also look forward to it. To look forward to having dinner with a dear friend, to holding space for the joy, love, and grief we have for our moms, to feel a little less alone on a day that can feel isolating as the rest of the world celebrates it.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Making Space to Hear Them: supporting children in grief

By Alyssa Warmland

Children tend to be naturally curious as they grow and learn to navigate the world. As adults, it’s our job to walk with them through that process of learning and to support their curiosity. It can be hard to do that with respect when we are situated in cultures that don’t acknowledge children as autonomous humans worthy of mutual respect. It can be tempting to encourage kids to ignore their feelings about death and grief or to shut down conversations about it when they ask questions. Sometimes, this is because we just don’t know what to say that is developmentally appropriate, especially with young children. Sometimes, it’s because we haven’t allowed ourselves to develop our own thoughts and feelings about death and grief and it feels uncomfortable for us to talk about.

What grieving children need from adults in their lives is to feel heard, just like adults do. When a child asks questions or talks about death or grief, here are some ideas of things to say and how to prompt conversations that allow us to listen:

– Tell me more about your ideas about dying. What do you think happens after someone dies? Those are good ideas, thanks for sharing them with me. I think [insert your own cultural or family beliefs about death].

– How are you feeling about [the being the child is grieving]? Do you want to tell me about some of your favourite memories about them? It’s okay to talk about it.

– It’s okay to feel however you are feeling. It’s okay to feel scared or curious about dying. You’re not alone. Do you want to tell me more about what’s going on for you? I love you and I’m here for you.

– Death isn’t something people can control, I want to make sure you know it’s not your fault [person/animal] died. Sometimes things just are and we can’t do anything about – them, but we can talk about how we are feeling about it.

It can also help to read children’s books about grief. Even if you don’t read them with your children, they might help give you the language to talk with them about death and grief when you’re not sure what to say. Most professionals recommend using direct language, such as “death”, “dying”, and “grief”, rather than terms like “passing away”, because they are easier for children to understand.

It’s important for children to know they’re not alone in their feelings and that it’s okay to feel hard things with the adults in their lives. Humans are social creatures who crave connection. Even when it’s hard or uncomfortable, pausing our busy lives to make that time for connection with children is important so they can learn how to process grief or whatever other feelings they’re having. It can also be an opportunity to re-parent ourselves. It might help to ask ourselves why we feel uncomfortable with a topic and what our own inner child might need to hear about the feelings that come up for us about death and grief. It’s important to seek out connection and space to process those feelings too, whether that’s through therapy or with other adults we trust to be vulnerable with.

Grief literacy and emotional literacy in general is worth making space for. Children have valid feelings worth expressing and being heard it’s it’s okay to stumble, imperfectly, within those conversations with them. Being with them is what is most important.

Additional Resources:

Kid’s Grief

Kids Help Phone

Children’s Grief Foundation

Children and Youth Grief Network

Children’s Grief Colouring Book

National Alliance for Children’s Grief

Bereaved Families of Ontario

Camp Erin

The Dougy Center

Kids’ books about grief:

When Dinosaurs Die

Badger’s Parting Gifts

The Fall of Freddie the Leaf

The Invisible String

The Heart and the Bottle

Healing Through the Holidays

by Lisa Hepner

The holidays can be hard if you’ve lost a loved one. But the holidays can also be a time to honour your loved one and heal. Here are a handful of things that may help you move through grief, and even find some joy, during the holiday season.

Decorate for Christmas. I know this can be hard. The first year after losing my mom I didn’t want to decorate. Heck, I didn’t even want to get out of bed. But I forced myself to decorate and once I started, I got into it and went all out. I know my mom would have wanted me to decorate. Christmas was her favourite time of year. So, I honoured her by decorating. And once the decorations were up, the beauty of the twinkle lights brought me joy. I also ordered a special memorial ornament for my mom and hung it up on the Christmas tree. That made me feel better. Like she was with me. But, if you’re not in the mood to decorate, that’s also okay. It’s important to honour where you’re at but maybe you can start with something small like some lights around a window or setting out a snow globe?

Every morning upon waking, state one thing you’re thankful for. When you’re grieving it’s hard to feel thankful. We often think about what we lost and not about what we have. But by acknowledging the good in your life, you attract more of it and you see more of it. You’ll soon realize that you have a lot to be thankful for, including the time that you did get to spend with your loved one and the memories that you have.

Volunteer for a cause. It could be for a one-time event or something that involves a regular commitment. I remember reading a quote by Richard Paul Evans that went something like, the best cure for a broken heart is to use it. This formed the premise a Christmas checklist that I made for myself and also wrote a book about. I love animals so I became a foster parent. If you love animals but can’t be a foster, you can volunteer to be a dog walker or a cat petter. The unconditional love of animals certainly made me feel better. Maybe you’d like to help feed the homeless? Donate to a women’s shelter? Read to kids? Volunteering, or giving, takes us outside of our own pain and drama and helps us feel like part of a solution. It feels good to give.

Find love. I know this may seem like a strange one but it’s based on a principle that says whatever you seek, you shall find. When a loved one dies, it’s hard to feel and see love. I thought when my mom died that the love we shared died as well, but it did NOT. That love will always be there. I started looking around for all the love I had in my life; the love from my husband, pets, brother, etc. The love and kindness of a neighbor or a stranger. Love is all around us, we just have to notice it.

If you’d like more suggestions, go to www.thechristmaschecklist.com for a free list of 12 things you can do to help you move through grief. But also know that you need to honor wherever you’re at. If you feel like lying in bed and crying, you must allow space for that as well. And it’s okay to seek help from a counselor or support group too (I did both). Hopefully, despite your loss, you will be able to experience some joy over the holiday season.

Calls to Care, Calls to Action: Bearing Witness to Global Catastrophic Loss of Life and Traumatic Events

By Jessica Milette, MSW/RSW

Human beings are wired for connection. Many of life’s most difficult experiences leave us feeling isolated, and connection can be a healing path. Currently, many of us are watching intense acts of genocide and death occurring internationally literally at our fingertips.

Why are our hearts tearing open at the witnessing of this pain? Why do we feel so helpless while we bear witness to pain and loss on massive levels that we may not feel entitled to experience because we are not directly impacted by these events?

In the words of a Jewish text, the Pirkei Avot “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.” And currently, there is so much grief in the world. Coming together in grief can be healing and a call for action to demand change in the face of oppression and genocide.

We bear witness to stories of mass loss of lives, stories of families in Gaza being forced from their land, loss of culture and traditions, and countless other ways systems of colonization and oppression can contribute to other non-death losses those who are directly affected currently and have historically faced. As we discussed in a previous article, we can also experience collective grief following natural disasters, accidents, international conflict, and acts of violence that have resulted in catastrophic loss of lives.

Loss also recognizes loss: hearing about international events that have resulted in the loss of lives, may have us thinking about our own losses in our lives. Depending on where we were born, the identities we hold, and how we move through our society can also impact our experiences of loss. We may be experiencing fear not knowing someone we love is alive who lives in an affected area. We may have experienced diaspora, and our communities in our home country are victims of violence. We can also feel grief deeply if we do not have a direct connection through our identities to those more directly impacted by the loss. Human beings are wired for connection and empathy – we hurt when we see hurt.

Some calls to care for when we experience collective grief:

– Being mindful of how much content you are consuming. It’s okay to step back or limit the types of information we choose to process. Perhaps reading articles from those who are directly impacted by these events feels more accessible than watching video coverage which can be graphic.

– Tend to your heart and body: the experience of grief can be demanding on our minds and bodies. Take time to rest, hydrate, and nourish yourself in healing ways. Caring for ourselves gives us more capacity to provide care to others we are in community with.

– Acknowledge your feelings. You may be feeling deep grief, despair, anger. It may feel easier to shut down these feelings, turn off our news feeds and burrow into our covers. But it is important that we give ourselves permission to feel and express our collective grief.

– Remember, POUR IN and DUMP OUT. Pour in support to those in your life who may be more directly impacted by these losses. Dump out your own grief to those who are not as directly impacted compared to your own positionality to these events.

– Grief AND joy can coexist. We can hold space to process our feelings of grief while also remaining open to experiences of lightness and joy.

– Share and express your feelings of grief with a supportive other. What types of support are most helpful to you when you have experienced grief?

There is power and healing in community. Collective action in moments of collective grief history have exposed injustice, and demanded action. We may also feel fatigued by the sheer volume of loss we are witnessing. When we feel fatigued, it can be easy to turn away and tell ourselves “this isn’t about me”. Turning away from these moments in history actually further silences those who are facing oppression, marginalization, and loss on a grand scale. Collective grief invites us an opportunity to gather collectively as a community to offer support, heal, and advocate.

Engage how you can. Everyone’s capacities will be different, and each of these things can help change our perspectives or ask for change:

– Learning and UnLearning about the topic

– Gathering in community through teach-ins, demonstrations, community vigils, or protests

– Create space for joy as we call for action. Could you host a movie night where you and supportive others write to local governmental representatives? Have a craft night to make signs for a local demonstration.

– Reflecting on our own experiences from a lens of critical self-reflexivity.

– Holding space for difficult conversations with loved ones

– Being critical as we read information – whose story is being centered, where is this source from

– How could I use the privilege(s) I have to amplify marginalized voices in this space?

Unlearning is uncomfortable. It asks us to sit and critically examine how our identities shape our view of the world. Taking stock of how your privileges or silence may have made you complicit in moments of oppression and marginalization. It may challenge your entire worldview. These things are uncomfortable. Discomfort is not a “bad” feeling – it is something that is uncomfortable to sit with. But sitting with our discomfort and increasing our tolerance to hold these uncomfortable feelings as we unlearn is part of this work. And it is so needed. We all have gifts of the head, heart, and hands we can lean on in times of collective grief, and in times we demand collective change.

Keeping Records

By Alyssa Warmland

I pulled the photos out of their envelope one at a time, turning over each one to carefully record the date, place, and people in the photo. Sometimes, I included comments. “Apple picking in Hamilton with Pop Pop, Fall, 2023. You loved the wagon ride!”. I slipped each picture into an empty pocket in my son’s photo album.

Next, I pulled out the baby book I’ve kept since before he was even earthside. I flipped to a page at the back to record an appointment, a new adventure with a forest homeschool group, and milestones.

When I tell other people my age about these rituals, they tend to share that they wish they were better about printing pictures and writing in their kids’ baby books. I’ve always enjoyed documentation, an avid journalkeeper as long as I’ve been able to write. I’ve considered this another extension of that interest. It wasn’t until earlier this week that it hit me- I keep these records so that if I die while my kid is young, he will have access to this information.

When I was 14, my mom was diagnosed with terminal cancer. I remember the day my dad picked me up from school and told me the results of the biopsy. I remember riding beside him in the passenger seat and thinking, “She’ll never meet my kids. She won’t be at my wedding. She won’t see me graduate.” All the milestones we would spend apart ran through my head. In the years since her death, I’ve consulted my baby book and read, over and over, the notes she wrote to me.

When my son was born and I became a mother, I read the notes in my book. When he started getting teeth, I turned to my (and my brother’s) books to find out when we got our teeth. I’ve looked up when we potty trained, what our sleep was like, about her breastfeeding experiences, when we started going to the dentist, and, most recently, upon learning that I was expecting another baby, what it was like when my mom brought my brother home. Not all, but some, of my questions I wish I could ask her about were answered in this record she lovingly kept.

As I write in my son’s books and caption the photos I’ve printed, I honour her, my child, and my own mother/child self. I hold space for my grief and for her memory. I continue a tradition of mothers keeping records to pick up when our babies need them.

Jessica’s Reflections as an Adult Grieving Child

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

November is considered Bereavement Awareness Month, and this year November 16 commemorates Children’s Grief Awareness Day. 1 in 14 children in Canada will experience the death of a parent or sibling by age 18.

The first funeral I attended was at the age of 7 when my Nana, or paternal grandmother died. My family buried my maternal grandfather 7 years later after he experienced a stroke when I was 14 and my mother was still in treatment for cancer. 13 months later, I would be burying my mom at age 15 after dying of cancer. She was 49. We would be gathering again less than two months later to bury my godmother and aunt who died suddenly and unexpectedly. Every time I felt like I had found footing on the shores of my grief, another loss would crash over me like a wave, dragging me out to a sea of unknown.

Navigating puberty can be an exciting and challenging transition in our life that also can have us feeling grief from non-death losses as we figure out who we are becoming. Not only was I trying to make sense of hormones and changes during this time of life, but my mom – the person who I would have gone to for support was no longer a phone call or hug away. Parents or trusted adults are people children often turn to for support, but my circle of trusted adults was shrinking. My peers were focused on what to wear on civvies day (a day where we didn’t have to wear a uniform), while I was focused on just surviving.

I felt so alone in my grief, although my twin, younger brother, dad, and other relatives in my life were also grieving. Friends would try to show up for me, sometimes it didn’t land well. There are friends who had never been to a funeral that walked with me in the depths of my grief who still hold a special place in my heart and life. I felt like I was in a sea of students in the hall between class with a flashing neon sign that read “Human with all the dead people in their life”. At times I could tell how awkward both peers and adults in my life were when approaching me – what do you tell someone when you’ve never experienced a death? And the person who is grieving can’t even legally drive a car!

There was no right or wrong way for me to grieve, but I had to find my own way to grieve. Sometimes they were helpful, and other times the things I did I thought helped me with my grief were not so helpful.

I am fortunate that despite the not-so-careful caring people in my life that made me feel invalidated, I had many caring adults in my life who let me know that grief is natural, and let me share stories of my loved ones. Within the first year of our loss, each of my siblings, my father, and I attended a grief support group. Walking into my first group was both scary and exciting: other teens like me?! The peer volunteer who co-ran these groups was actually someone I knew personally, but had no idea that they had been touched by death too.

I felt deep sadness, guilt, and anger in that group. I also felt deep connection, joy, and even laughter. We got to talk about our sibling, parent, or other close person in our life we were grieving. Talking about grief didn’t make me feel more alone, or worse, it made me feel LESS alone. That we all grieve what we are connected to. That’s it’s okay to not be okay. That sharing our stories of our person and our pain can be healing when we have the right kind of listener in our corner. And that we never have to walk alone at any age or stage of our grief.