Posts Tagged ‘Grief’

Always Kiss Me Goodnight : Deborah Dickson

Deborah Dickson recently released a book about grief for children called Always Kiss Me Goodnight. She recently reached out to us at Grief Stories to share a bit about it and the accompanying guidebook for parents and teachers who support kids in grief and we are honoured to share a bit more about this important resource.

Deborah’s mother, Wanda Marie McLaughlin, passed away at age 39 on November 8th, 1974 when Deborah was 19 years old. Her search for understanding and “figuring out what was missing” in her life, turned on an awareness switch. There was more behind this awareness than she realized.

Grief Stories: Tell us a little more about your experience writing Always Kiss Me Goodnight.

Deborah: “Always Kiss Me Goodnight” is based on my true story of heartbreak stemming from the loss of my mom when I was a young adult. I felt responsible for my three brothers, helped with household chores, and worked full time all while trying to navigate my grieving journey.

Writing this book was amazing, tearful, and filled with learning. It was gratifying to be able to share my personal story with children alongside the wonderful digital illustrations by our grandson Ronan to correlate with the story. Keeping the storyline simple but real and informative from my perspective was an amazing learning and therapeutic journey. I am forever grateful for the writing opportunity and for the strength I learned from my Mom. I cherish our family memories. It furthers my belief in being kind and helping others.

I wrote this book about grieving to help others (and myself) acknowledge and understand the challenging and painful emotions one has following the loss of a loved one. I emphasize the importance of asking questions, the never-ending search for answers, and not being afraid to ask for help – these were the pieces I learned from my own journey.”

Grief Stories: Based on your personal experience, what recommendations do you have for parents who are supporting children in grief ?

Deborah: “‘Family’ to me is ‘everything’.

Tragedy can cause so much grief and sadness that family members may fail to recognize each other’s emotions and needs – especially children’s. While it is important to try to be strong, it is also important for children to see a parent’s sadness and tears. Age-appropriate communication is also important, children need to be included in planning and have an understanding of what is going on. It’s important to provide a safe environment for the children to talk about the loss, even if it’s not with you.

People can support children by allowing them to express whatever emotion they are feeling without judgment. If the family is beyond knowing what to do for themselves or their children – reach out for professional help. Don’t continue to be afraid or alone, it is healthier for all to reach out.”

Grief Stories: As is relates to the parent/teacher guide you created to go alongside your book, what are the key tips for supporting children.

Deborah:

- Parents may want to protect their children from painful grief emotions by hiding their emotions. However, it is important that parents take time to recognize, acknowledge, and express their grief in healthy ways. This lets parents honour their own grief needs, while also modeling healthy coping behaviours for their children.

- Communication is vital, reassure them that you or someone else is always available to come to.

- Focus on reassurance, family memories, recall vacations and pictures. Encourage them to draw, make a scrap book, or a collage.

- If you don’t have an answer for them know that that is okay – you ask for help – reach out to professionals and don’t feel that you are all alone dealing with the grieving process.

- Talk to them, hug them, tell that they are loved, that they are heard and they are safe.

Losing my Mom at an early age has impacted my life in so many ways. I wanted to share my story and other resources to help parents and children, should they face a tragedy like the loss of a loved one. I hope that this book can be of some service and an avenue to explore difficult conversations. May you enjoy “Always Kiss Me Goodnight” and hug your family tight and often.

You can find out more about Deborah and “ Always Kiss Me Goodnight “ through her website https://www.neversaygoodbye.ca/home.

Who are we to Decide? The Many Paths through Grief

A lot of my work with clients involves hearing their stories, but also answering many questions about if their grief is “normal”. Their grief is overwhelming, and our dominant culture’s strong message is – that grief should be kept at its edges, I often find this pervasive intention creeps into griever’s experiences – and my worldview at times. I even catch myself apologizing for crying in public spaces, shutting down my process. There are many ways of doing, being, and knowing, which I continue to learn through the spaces I hold with others.

A Ghanaian woman living in Canada shared with me her experiences after the death of her mother who died in their home country of Ghana. Traditionally, when someone dies in their community, their body is laid in the home and the entire community is welcomed. Feasts, songs, stories, cries, wails. Their world stops – and for longer than a mere few hours. Loud, open expressions of grief are honoured and welcomed.

A Chinese woman expressed worry that something was wrong with them. After attending a grief support group, she felt worse rather than better. So many people have shared how helpful these spaces had been for them, but this wasn’t her experience at all.

A White man sits across from me and tells me his wife encouraged him to try therapy because “he isn’t grieving” since he doesn’t openly share his emotions. One finds comfort in storytelling, talking about the loss of their child, and finds crying cathartic. He speaks about the qualities and memories of their child, practical matters over emotional ones, and their passion for bringing forth advocacy and change concerning the drug poisoning epidemic.

An Indigenous woman speaks about a ritual in their community where the grieving family cuts their hair after a loved one’s death. On one hand, they feel guilt at times for not engaging with it because it “makes it real”. However, getting a tattoo of a flower they got after their mother’s death was their ritual.

In North America, we are quick to try to “fix” or “solve” grief. There are many books, support groups, and online communities about grief. Yet I have had more than a handful of clients who have recently experienced a death share how their doctor offered them a psychopharmacological medication before their doctor may even acknowledge their loss. I think about the Ghanaian woman, and how open and welcome grief is within their local community. I can only imagine how stifling tending to these rituals in North America may have felt to this person if their mother died in Canada.

There is no “magic pill” to prescribe, but I know many people in the depths of their grief wish there were something, anything to “fast forward” through the sleepless nights, waves of emotion, and grief bursts to a place where their grief feels less overwhelming. There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

Here are some gentle prompts for you to explore some ways to tend to your grief:

What brings meaning or comfort, to you?

Are there particular rituals your community (spiritual, ethnic, other identities) find important to help honour your loved one?

Which rituals do you find comforting but at times find it difficult to share with others?

Just because White colonizer culture is dominant in North America, does not mean those perspectives are “the right way” through grief and loss. There are many ways of being, doing and knowing in life and in grief.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Holding Space for The Many Faces of Grief on Father’s Day

A lot of blog posts and articles about grief and special days tend to focus on how to navigate these moments when our loved one has died. Often these articles of grief also talk about the ways we have deeply loved or cared for the person who has died.

Grief is a natural response to when we lose someone or something we have had a connection to. So what happens for the grievers who have had a not-so-loving relationship with the person who has died, or has experienced an estrangement?

I’ve heard folx sitting across from me talk about how surprising it was to experience a surge of emotions after finding out their father died after being estranged for half their life. Another person talked about how frustrating it was to hear others ask them why it didn’t seem they were grieving, and that they “should” be more tearful because their father had died, however, these people did not know how difficult their relationship with and to their father was when he was alive. Someone else shares how hard it is to carry the grief of deciding to estrange themselves from their father.

To those of you grieving and/or approaching this Father’s Day with complex feelings and memories of a not-so-loving relationship: you are not alone. We grieve because we have had a connection – and a connection can be filled with many things. Love may be part of these connections in our life, but so many other complex emotions, and situations can be part of these connections. People are complicated. Love is complicated. Grief is also complicated.

We can grieve that we did not have the relationship with the person we needed, grieve the parts of the person we miss, or even grieve for a future where perhaps we may have been able to repair the rupture in our relationship.

Grief can feel even more complicated when we have a complex relationship with the person we are grieving. It can make us feel even more isolated. Disenfranchised Grief is any type of grief where society has denied the griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. When a relationship has been not-so-loving we may hear well-intentioned people telling us ‘You shouldn’t feel grief because X was not a good person or not a big part of your life’. Our society also tends to prioritize grief experiences through death, and not non-death losses like an estrangement from a parent.

Whether your father has died and you had a complex relationship with them, are grieving the living relationship with your father you never were able to have, or grieving an estrangement from your Father your feelings are valid. Grief is not just one emotion, but is a natural response that can have many different emotions depending on the person. It’s okay if you feel anger, frustration, regret, guilt, and even relief. Special days where all we hear and see are advertisements talking about Father’s Day can bring up extra waves of grief as we near this date.

Here are some gentle reminders if you are moving through Father’s Day this year and have a complicated relationship with your father, or paternal figure in your life:

- Give yourself permission to write a letter to this person, expressing the things you never have been able to say. It can be a place to put down all those thoughts and feelings that you can then release. Feel free to rip this letter up into a tiny pieces, flush it down the toilet, or even safely burn the page.

- Spend time that day however you need to and with people who support you.

- Our biological family is just one connection we have, but we also create our own “chosen family” of close relationships. You may feel compelled to send a card or write a note to someone you feel creates a paternal presence in your life like a good friend, mentor, or another relative.

- Allow yourself rest as you move through the day as grief can be an exhausting experience on our minds and bodies.

Maybe you’ve lost your father or father figure to death, or you’ve lost your father figuratively because of dementia, or you’ve lost your father in your life because of his unacceptance of your lifestyle. In whatever case, you’re not alone.

However you navigate this day, know this:

- If you feel happy, that is okay

- If you feel sad, that is okay

- If you feel angry, that is okay

- If you feel a roller coaster of emotions, that is okay

- If you feel nothing, that is okay

- If you don’t WANT to feel anything today, that is okay

The reality is that no one can tell you how to feel about your situation.

Your feelings are valid. However you choose to be, honour that, honour you.

Creating Mother’s Day Traditions as a member of the Dead Mom Club

About a week after Easter this year, I noticed I was starting to feel off. My sleep wasn’t as restful, experiencing tension in my body, at times I was getting irritated with the simplest things. Then while streaming an episode of television, 4 ads back to back all talking about Mother’s Day. Then came the promotional emails, the store displays, and even a banner at the top of my Microsoft Word app directing users to their Mother’s Day templates.

Each year, my relationship with Mother’s Day has changed and it will likely continue to transform for the rest of my life. Early in my grief, I avoided any reminders. It was so difficult to work my part-time job in high school with Mother’s Day displays all around me, hearing about patrons’ plans, and then being asked how my own family would celebrate. I would feel my grief weigh heavily on my body, wanting to sleep until June 1st if I could. My first few Mother’s Days were about survival mode, and getting through my waves of grief.

Photo of Jessica and her mother, facing the camera and smiling.

I’m not crushed by my Mother’s Day grief these days in the same way, but I know it is a time of year for me when my grief can show up more. Thoughts about what she would think about streaming platforms; the things I want to tell her; the things I want to thank her for. As my grief has changed these past 18 years, I’ve written letters to my mom, worn pieces of her jewelry, visited her gravesite, bought and written a Mother’s Day card she would have liked, and made some of my favourite childhood recipes of hers.

I would spend many of my Mother’s Days with my grandmother, my mom’s mom as I knew that day held its difficulties for her too. As my grandmother’s health declined over the pandemic, I wasn’t always able or allowed to visit with restrictions. After she died in 2021, I was in a fog by the time Mother’s Day 2022 came around. It felt surreal to me, that on my mother’s side – there are no longer any living maternal presences in my life.

Photo of Jessica wearing a blue satin dress and her mother wearing a long black and

white floral jacket , holding hands as if they are dancing for the camera.

Last year, a friend and another member of the Dead Mom Club were talking about how much this time of year can impact us. These conversations led to something surprising, and beautiful, but also a new tradition that I look forward to engaging in this year. Last Mother’s Day, we had dinner at a nice restaurant downtown, dressed up, and spent an evening talking about our moms. I wore a skirt that belonged to my grandmother and some jewelry that belonged to my mom. My friend also shared items they were wearing or keeping with them that reminded them of their mom. We laughed, we cried, we hugged. It was so cathartic to talk about the things some of our other friends couldn’t quite understand. At times dreading that 2nd Sunday in May, I now know that I can hold space for the difficult emotions that may arise and that I can also look forward to it. To look forward to having dinner with a dear friend, to holding space for the joy, love, and grief we have for our moms, to feel a little less alone on a day that can feel isolating as the rest of the world celebrates it.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Pet Loss: When People Fall Silent

A few days after the birth of my younger brother, my father was taking the dog he and my mother adopted from the humane society, along with my twin and I, to the veterinarian. Years later, my father would share how many times he wiped his eyes on the car ride there. Yoda shared 16 years of her life with my parents. She was there when they went from a family of 3 to 5, and at my mother’s side as we were preparing to welcome our younger brother.

Clifford was just under a year old at the time we said goodbye to Yoda. He and my mom were thick as thieves. He’d keep her company while we were at school, dad was at work, and in her most difficult moments as her cancer progressed.

Clifford was about 9 years old and had a history of health complications before my mother’s death. After her death, we knew he was grieving too. He would search her out, but he began to slow, and other health factors started to creep in. We were just starting to thaw out from the depths of our mother’s death. And now another loss six months later?

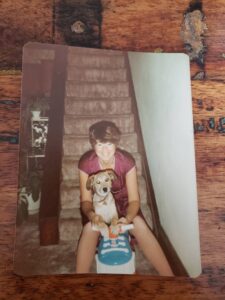

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Both are sitting on the stairs Jessica’s mother is smiling for the camera holding Yoda in her lap

Why do we question ourselves, and our grief when it comes to pet and other animal losses? Grief is the natural response when we face the loss of something or someone we have a connection to. The grief we feel after a pet dies is a natural response to their loss given the unique relationships we have with our pets. The humans in a pet’s family may be the only ones they know and love in their lifetime. We can experience grief bursts as we navigate this loss: instead of our grief showing up when our loved one no longer walks through the door at 6:00 pm after work, it may be each time we come home and don’t hear their paws hitting the ground as they race to greet us.

Roxy was our first dog a few years after Clifford and my mother’s death. It also felt strange: excited to have a dog again, while also feeling pangs of grief for Clifford. We can hold space for new love, while also still experiencing moments where we miss our old pets who we loved just as equally.

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

When Roxy was 13, our vet had noticed changes in her health typical for a dog her age. Every time I came home to visit I’d savor my time with her, and wonder, “Would this be the last time?”. A year later, Roxy was now no longer eating or drinking as often, and the vet felt her decline was her way of telling us she was ready to go. She indulged in poached salmon for her final dinner. Early one summer afternoon, my dad sent our family a photo of him lovingly holding Roxy in his arms and looking into her eyes. The note said she had passed onto the rainbow bridge, and he gave her extra hugs from all of us. I held space for the relief that she was no longer in pain, and the grief that I would never give her a belly rub again.

These are just some of my stories, and those reading this may have stories too. The tales where they did something ridiculous. The time they were there for you in your highest highs and lowest lows. The first time you met them. The last time you held them.

It’s important we hold space to share our stories but it can be difficult when pet and animal loss is a form of disenfranchised grief. Disenfranchised grief refers to when society denies a griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. This can leave us feeling even more isolated as we grieve. North American settler culture tends to prioritize human death loss over animal loss. But that doesn’t make your grief any less valid. Your grief may come in waves, be gentle with yourself as your body goes through this natural process.

You may experience shadowlosses and secondary losses related to the death of your pet.

I felt a pang when I didn’t hear the clinking of Roxy’s dog tags, expecting her to slowly saunter into the hallway my first visit back after her death. My parents felt lost with what they should do with pet care supplies they couldn’t donate. Many friends where I live have pets and I was able to share some of Roxy’s most treasured items with them, something Roxy would appreciate. But the choice tugged at my heartstrings as I removed these items from my family home.

Each unique bond with our pet is carried within us and you are allowed to honour it in whatever way makes sense. It may be having photos of your pet up in your space. Honour old traditions of your old pet with your new pet – if or when you choose to welcome a new pet into your life. Share stories of your special furry, feathered, fluffy, or scaly pet with your circle. Our stories can help us feel connected to them, and also feel less alone in our grief.

There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

______________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Grief, Exhaustion, & Rest

Many people consider grief to be a response to the death of a loved one, but we grieve so much more than that. Grief is an emotional response to loss of any kind. Both real or perceived loss can trigger the response. The loss of a job, a miscarriage, a breakup, losing a sentimental item, or big life changes like moving can all cause grief.

Grief fatigue is a very real thing. Even though we know that grief is a healthy response to loss, it’s perfectly normal to get tired of it. You’re not in intense pain, but it also isn’t getting any easier yet. It’s exhausting. Grief exhaustion refers to the deep and pervasive fatigue often accompanying the grieving process. It goes beyond the typical tiredness we experience in our daily lives and stems from the immense emotional and psychological strain that grief places upon us.

Grief can leave you feeling drained, both physically and mentally, making even the simplest tasks seem overwhelming. Even typical activities can feel like too much when our physical body and brain refuses to cooperate. The mind and body are closely connected and the grief process is a good example of that. The mental and emotional toll of grief can wreak havoc on a person’s mental and physical well-being.

Emotions are not always easy to deal with and having intense ones can be incredibly draining. Grief is a complex emotion that can be mentally and physically taxing. The profound sadness and range of emotions experienced during the different stages of grief can lead to fatigue and exhaustion. Even though you’re tired, you may have trouble sleeping or sleep a lot and never feel rested.

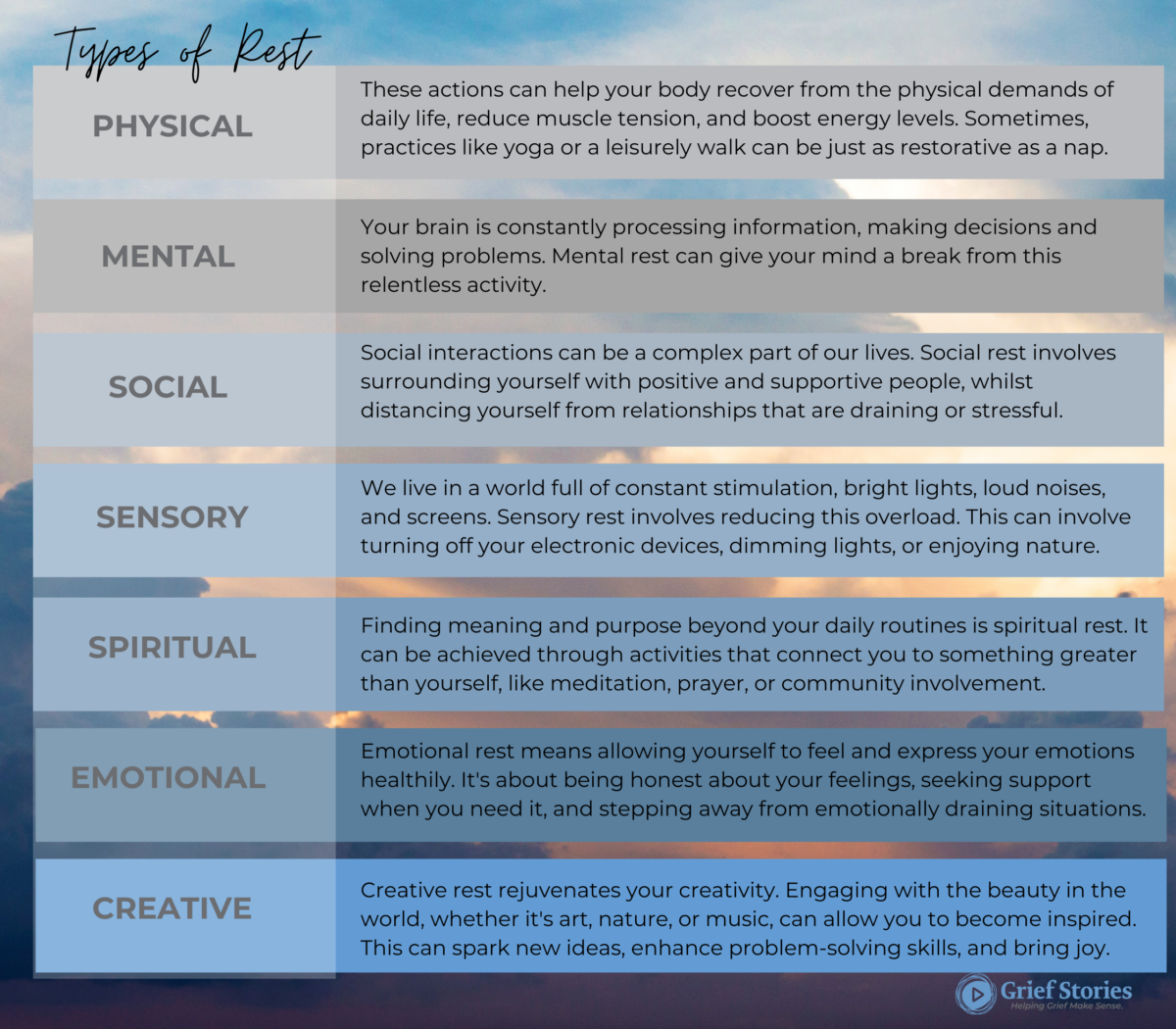

We often blame grief exhaustion on sleep deprivation—and that is a component. Sleep is essential, and needs to be prioritized. But, so many of us still feel exhausted and burnt out even when we finally start sleeping. Grief exhaustion isn’t solved with more sleep. Dr. Saundra Dalton Smith says we need seven types of rest. As I read her work, I find it especially applicable to grief.

Dr. Saundra pointed out that taking a comprehensive approach to rest is a bridge to better sleep and this is handled with attentive self-care. When we talk about rest outside of sleep, our minds might immediately jump to stereotypical “self-care” activities, like getting a massage or taking a bubble bath. Real self-care is nurturing our current needs. We might need to rest mentally, or to reconnect with our friends, or to be vulnerable with our emotions. Our needs are often rooted in the types of rest and what we’re lacking.

Being able to pinpoint what you and your body need in terms of rest will allow you to address the area and choose a restful activity that fits your needs.

When we understand the types of rest, we can become better aware of our own needs and make small changes in our lives that leave us feeling more whole, more energized, and more refreshed.

Making Space to Hear Them: supporting children in grief

By Alyssa Warmland

Children tend to be naturally curious as they grow and learn to navigate the world. As adults, it’s our job to walk with them through that process of learning and to support their curiosity. It can be hard to do that with respect when we are situated in cultures that don’t acknowledge children as autonomous humans worthy of mutual respect. It can be tempting to encourage kids to ignore their feelings about death and grief or to shut down conversations about it when they ask questions. Sometimes, this is because we just don’t know what to say that is developmentally appropriate, especially with young children. Sometimes, it’s because we haven’t allowed ourselves to develop our own thoughts and feelings about death and grief and it feels uncomfortable for us to talk about.

What grieving children need from adults in their lives is to feel heard, just like adults do. When a child asks questions or talks about death or grief, here are some ideas of things to say and how to prompt conversations that allow us to listen:

– Tell me more about your ideas about dying. What do you think happens after someone dies? Those are good ideas, thanks for sharing them with me. I think [insert your own cultural or family beliefs about death].

– How are you feeling about [the being the child is grieving]? Do you want to tell me about some of your favourite memories about them? It’s okay to talk about it.

– It’s okay to feel however you are feeling. It’s okay to feel scared or curious about dying. You’re not alone. Do you want to tell me more about what’s going on for you? I love you and I’m here for you.

– Death isn’t something people can control, I want to make sure you know it’s not your fault [person/animal] died. Sometimes things just are and we can’t do anything about – them, but we can talk about how we are feeling about it.

It can also help to read children’s books about grief. Even if you don’t read them with your children, they might help give you the language to talk with them about death and grief when you’re not sure what to say. Most professionals recommend using direct language, such as “death”, “dying”, and “grief”, rather than terms like “passing away”, because they are easier for children to understand.

It’s important for children to know they’re not alone in their feelings and that it’s okay to feel hard things with the adults in their lives. Humans are social creatures who crave connection. Even when it’s hard or uncomfortable, pausing our busy lives to make that time for connection with children is important so they can learn how to process grief or whatever other feelings they’re having. It can also be an opportunity to re-parent ourselves. It might help to ask ourselves why we feel uncomfortable with a topic and what our own inner child might need to hear about the feelings that come up for us about death and grief. It’s important to seek out connection and space to process those feelings too, whether that’s through therapy or with other adults we trust to be vulnerable with.

Grief literacy and emotional literacy in general is worth making space for. Children have valid feelings worth expressing and being heard it’s it’s okay to stumble, imperfectly, within those conversations with them. Being with them is what is most important.

Additional Resources:

Kid’s Grief

Kids Help Phone

Children’s Grief Foundation

Children and Youth Grief Network

Children’s Grief Colouring Book

National Alliance for Children’s Grief

Bereaved Families of Ontario

Camp Erin

The Dougy Center

Kids’ books about grief:

When Dinosaurs Die

Badger’s Parting Gifts

The Fall of Freddie the Leaf

The Invisible String

The Heart and the Bottle

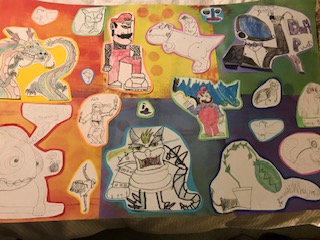

Doodles

By Betsy Fisher

Surviving.

Wading into all the “firsts” I never wanted to see.

On the first anniversary, I invited people who would understand – friends who knew Marshal’s love of art, and his creative spirit. They all came.

I had copied several of Marshal’s doodles of incomplete characters and creatures, with some finished for the kids to color. I eagerly watched to see which doodle or drawing each person chose.

“Hey! That looks like Abraham Lincoln! I want to finish that one.”

“Cool…look at this giraffe! I want to color this one!”

“Whoa, what a cool monster!”

“What is this one?! I think it’s some kind of frog.”

The children sat in the kitchen table or on the porch, clutching crayons with great care and the grownups chose doodles and pieces of something larger, saying, “Oh, yes, Marshal would have loved this.”

People smiled as they drew or colored. I found myself smiling, too, even laughing now and then. I walked among them and as I watched them, I felt things I had not felt before, things I could not name.

I had stressed over “what to do” to mark this date, one year later, where ending and beginning would meet. Marshal took ordinary, simple things, and created magic.

Among the many doodles was one of a man-eating plant. A Venus Flytrap like the one from “Little Shop of Horrors” but with a face and personality of its own. It is stretching over and about to swallow up a stick figure. “Oh snap!” says the figure. “Why me?!”

An 8-year-old boy chose that drawing to color. The little hero had miraculously survived cancer as a toddler, and now he was a full-on, healthy, nothing-but-smiling little boy. We met him, and his mother, at Shands, and we grew to know and love them well in the years to follow.

He remembers Marshal a little – his famous fart sounds, character voices, and artistic creations. Their shared love of Mario. He carries his lunch to school today in Marshal’s Mario backpack. He was so excited to get started.

His picture was so colorful and he showed it to me with such pride. I told him more than once just how much Marshal would have liked what he had done with it.

They all seemed to know how important it was to me. They seemed to know Marshal would be there, too. And he was.

As I took it all in, Marshal seemed so strangely present. I felt a different “alive” than I had felt in that first terrible year of grief. He was my smile, the lump in my throat with every hello and goodbye. He was the twinkle in my eye as I saw their love, as I immersed myself in this afternoon.

I hadn’t been sure I could handle the laughter, or making this saddest of days a happy one, somehow. But I could, and it was.

Many of them left their doodles for me to keep or sent pictures after finishing them at home. A friend took them all and made a simple collage, now in my room.

It is love carrying on. It is my proof. Living proof that just as more can be made from these incredible beginnings of doodles and sketches, more can be made from my story with Marshal. Maybe I can move forward, bringing him along with me.

Legacy. Life. Continuity. Connection.

Always and every day.

If you’d like to draw and color with Marshal’s doodles, email Betsy at marshalsdoodles@gmail.com.

Grief Busting Zine [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. We’re sorry you’re feeling this way right now but so glad you’re reading this.

This zine is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

Physical copies of this sine were originally distributed at Cultivate Festival in 2023.

Community Grief Toolkit [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in the community. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and how to build the resources for further support.

Download it here.

What is a Toolkit?

Grief Stories strives to create a free, accessible, diverse, inclusive, on-demand resource, reducing barriers to accurate online information about grief, helping grievers and those who support them using innovative technology. Our toolkits curate our multimedia content into an easy-to-navigate format on different topics, all vetted by healthcare professionals with expertise in grief and loss.

Toolkits are a popular knowledge translation strategy for disseminating health and wellness information, to build awareness, inform, and change public and healthcare provider behaviour. By keeping our content and toolkits free to access, we help individuals feel confident in connecting with and supporting grievers in their life, while at the same time providing accurate information about grief to help grievers make sense of their experience, one story at a time so they feel less alone.

As a virtual organization, we envision a world connected and supported in grief through our free multimedia library of content. Grief Stories relies on donations to cover many operational costs, including content creation. Each donation we receive allows us to share even more stories, helping grief make sense. If you, or someone in your life has found one of the toolkits helpful, please consider making a suggested donation of $10.00.

For less than the price of a premium streaming service, you can help us share our stories even further with those who need them most – helping grief make sense, one story at a time.

Healing Through the Holidays

by Lisa Hepner

The holidays can be hard if you’ve lost a loved one. But the holidays can also be a time to honour your loved one and heal. Here are a handful of things that may help you move through grief, and even find some joy, during the holiday season.

Decorate for Christmas. I know this can be hard. The first year after losing my mom I didn’t want to decorate. Heck, I didn’t even want to get out of bed. But I forced myself to decorate and once I started, I got into it and went all out. I know my mom would have wanted me to decorate. Christmas was her favourite time of year. So, I honoured her by decorating. And once the decorations were up, the beauty of the twinkle lights brought me joy. I also ordered a special memorial ornament for my mom and hung it up on the Christmas tree. That made me feel better. Like she was with me. But, if you’re not in the mood to decorate, that’s also okay. It’s important to honour where you’re at but maybe you can start with something small like some lights around a window or setting out a snow globe?

Every morning upon waking, state one thing you’re thankful for. When you’re grieving it’s hard to feel thankful. We often think about what we lost and not about what we have. But by acknowledging the good in your life, you attract more of it and you see more of it. You’ll soon realize that you have a lot to be thankful for, including the time that you did get to spend with your loved one and the memories that you have.

Volunteer for a cause. It could be for a one-time event or something that involves a regular commitment. I remember reading a quote by Richard Paul Evans that went something like, the best cure for a broken heart is to use it. This formed the premise a Christmas checklist that I made for myself and also wrote a book about. I love animals so I became a foster parent. If you love animals but can’t be a foster, you can volunteer to be a dog walker or a cat petter. The unconditional love of animals certainly made me feel better. Maybe you’d like to help feed the homeless? Donate to a women’s shelter? Read to kids? Volunteering, or giving, takes us outside of our own pain and drama and helps us feel like part of a solution. It feels good to give.

Find love. I know this may seem like a strange one but it’s based on a principle that says whatever you seek, you shall find. When a loved one dies, it’s hard to feel and see love. I thought when my mom died that the love we shared died as well, but it did NOT. That love will always be there. I started looking around for all the love I had in my life; the love from my husband, pets, brother, etc. The love and kindness of a neighbor or a stranger. Love is all around us, we just have to notice it.

If you’d like more suggestions, go to www.thechristmaschecklist.com for a free list of 12 things you can do to help you move through grief. But also know that you need to honor wherever you’re at. If you feel like lying in bed and crying, you must allow space for that as well. And it’s okay to seek help from a counselor or support group too (I did both). Hopefully, despite your loss, you will be able to experience some joy over the holiday season.

Jewish Perspectives on Grieving

Reflections by Richard Quodomine

You can read more of Rich’s reflections on Jewish perspectives on grief here.

What is Jewish Grieving? All humans can, and should, grieve over loss of life during a conflict. No matter the beginning or the end, all violence ends with grief. Someone’s grandparent, parent, sibling or child will die. That cycle of violence must cease.

Our faiths or cultural traditions are what help us give structure to that grief. “To not have felt pain is to not be human,” is a traditional Jewish proverb. Our humanity should also ask that we grieve even the people we assume to be our opponents in a conflict. This does not mean a failure to assign responsibility to those who cause harm, but rather to recognize that often, those intending harm come from a small cadre of leaders, with many others in service to it. When you become a warrior with a hateful cause, you can lose sight of the humanity of others.

One type of grief is the personal loss of a loved one, for which there is a proscribed period of mourning. Recently, though, we reflect on a different kind of grief, the kind that is not about personal loss. Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, in the Forward, spoke of the current conflict this way: “To grieve over the Israeli victims does not preclude grieving over the loss, too, of innocent Palestinian lives. Human as it is to lose sleep thinking of the well-being of the courageous soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces fighting in Gaza, it is inhumane to not also lose sleep at the thought of all the Gazans caught in the crossfire of war.” This is key to the Jewish concept of grief: it is inhumane not to grieve over innocent life lost – regardless of its culture, religion, or cause.

Maimonides, the 12th century Jewish scholar of Cairo, said this: “Whoever does not mourn the dead in the manner enjoined by the rabbis [lacks sensitivity].” While the inference is often ascribed to Jewish grief, Maimonides was a key court advisor and physician to Sultan Saladin. As such, he often wrote to Jewish and Muslim audiences and wrote in Aramaic and Arabic with equal faculty. He would tell his audiences to grieve in their own way – Jew, Muslim and others. Maimonides further tackled this in what he called the second of the three evils: “[these comprise] such evils as people cause to each other [when they] use their [strength] against others.” You can grieve the unjust use of force that causes the loss.

The word for peace – shalom, comes from the same Hebrew root word as shleymut, meaning perfect or whole.Thus, not being at peace is imperfect. We do not just condemn wrong in Judaism. It’s easy to say “that person / cause is wrong.” The harder part is fixing the damage, even if we weren’t the direct cause of it. That requires sensitivity and acknowledgement of loss. We should grieve the damage the conflict does to all involved. A common Jewish saying is “G-d is closest to those with broken hearts.” That gives all of us an opportunity to grow closer to each other in grieving.

According to Rabbi Simeon ben Gamliel, three things preserve the world: truth, justice, and peace

(Avot1:18). When we lay the guns and swords down, the hard work of peace begins. That work will

require productive grief – a grief that spurs us all to healing actions, kindness, and building bridges where walls once stood.

May we light Menorahs in Peace next year.