Posts Tagged ‘grief stories’

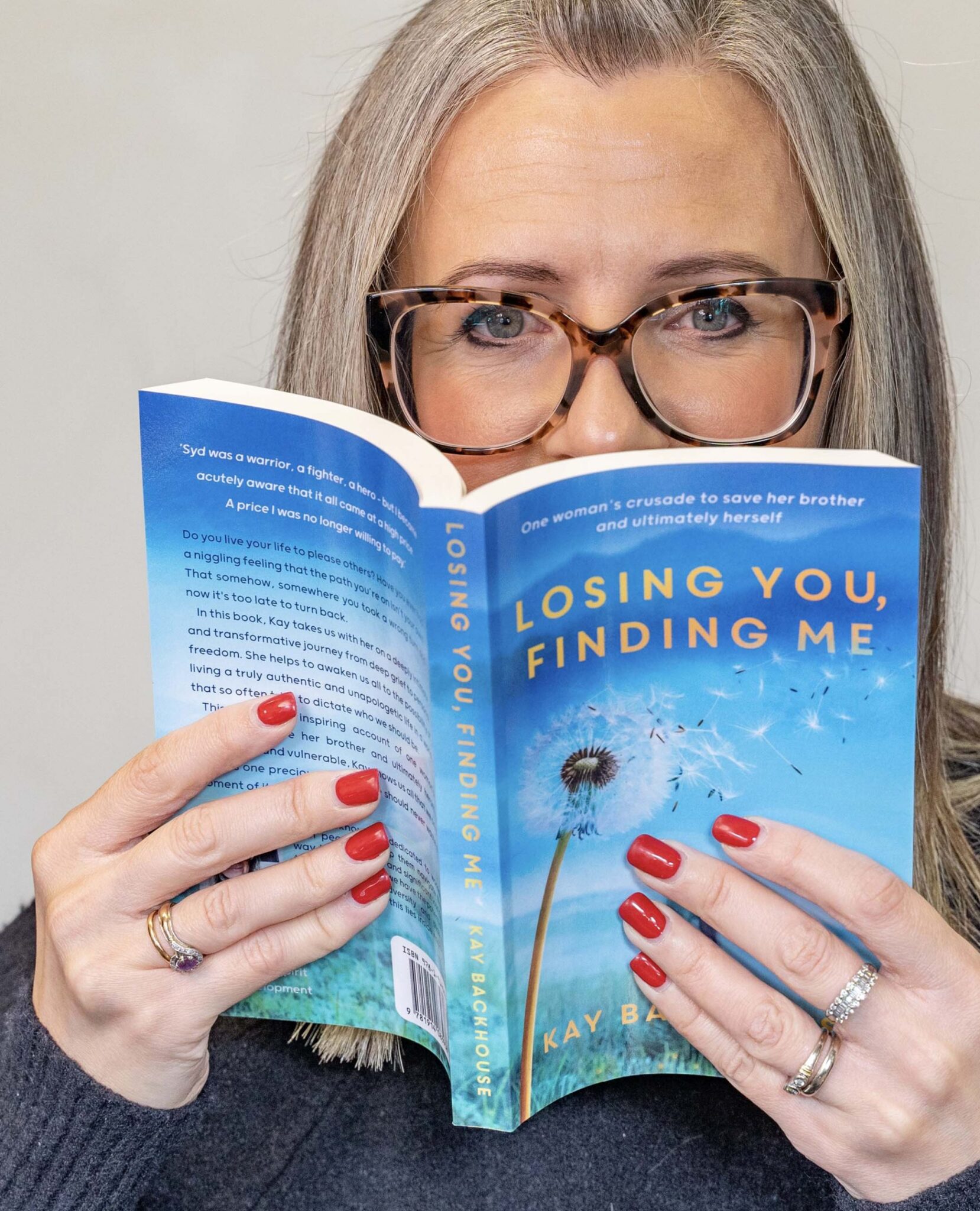

The ties that bind; grieving the loss of a sibling

When my three brothers and I were growing up and the proverbial hit the fan, Mum would often say, in a bid to keep her brood calm, ‘Well, at least we are all still here.’

She reminded me of this affectionate saying only very recently. I can still recall how I felt as a child when she said those words – a collective sigh of relief would ripple across our family unit and if I close my eyes tight enough as I type these words, I can still feel the tsunami of endorphins that quickly engulfed and soothed my young, innocent heart. I knew that in that moment – in the simplest of terms – that if we were all together, everything would be OK – nothing else mattered. It was us against the world. Until the day came when we weren’t all here anymore – and things were not OK. The day my brother, Louis Sydney Wilson died – 17th February 2019. The day when the six of us became five. When four siblings became three. The day when everything changed, and the earth seemed to flip on its axis.

Syd – as he was affectionately known from around the age of seven – was my little brother, four years my junior. He was the last person in my family that anyone would ever have expected to receive a cancer diagnosis, let alone a terminal one. Growing up he was the sensible one of the four of us. He rarely drank alcohol, never smoked, or took drugs, recreationally or otherwise, never caused my parents sleepless nights like the rest of us and was always, well……the golden child – you know the one – most families have one. He was the happy-go-lucky kid, funny, and intelligent – not that he would ever think that about himself. And even if he did, he would never say it aloud. Growing up he towed the line in all aspects of his life – he was never promiscuous, rarely answered back and was a ‘good boy.’ He would later comment as he was nearing the end of his life that this was half the reason he ended up sick. For whatever reason he never felt he could fully express himself and became trapped in what I refer to in my book Losing You, Finding Me, as the ‘invisible cage’ – his life became a product of what he thought others expected of him rather than being true to himself. A trap many of us fall into and struggle to get out of.

When he died, the loss felt unbearable. It was as if I was missing a limb. I struggled to make sense of anything for the first twelve months. I experienced what felt like a never-ending black hole of grief that I didn’t think I could ever climb out of and in all honesty, I wasn’t sure that I even wanted to – there were times I wanted to die with him. You see that’s the funny thing about grief, as much as it’s painful, it can feel like our only direct connection to the person that has died. Without the pain there is no love. In many ways the more pain I felt the closer I was to him. There is a saying that ‘grief is the price we pay for love,’ and I genuinely believe this – they come in equal measure.

The sibling bond is like no other – it’s an undeniable connection – we quite literally share the same DNA. When we look at our siblings, we often see aspects of ourselves – the parts we love and, annoyingly the parts we hate. It’s the only relationship where we want to push them off a cliff edge and yet catch them at the same time. I witness this playing out in my own sons lives. So, when one of them dies, it’s like a piece of ourselves has evaporated alongside them. The rich tapestry of family life seems to come away at the seams – memories forever altered – every family photo now incomplete.

Now, don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t all roses – we were siblings at the end of the day, and as with all siblings, we had our moments. But they were rare. When we didn’t agree, rather than argue, we would just drift apart like boats cast adrift at sea, not speaking for a few years at one stage, right before his shocking diagnosis. That diagnosis in September 2011 (on his twenty-eighth birthday) was like a bomb going off at the centre of the ocean – and although shocking and destructive, I will always be grateful that beyond the wake our boats were gently guided back to the safety of the shore. We were back where we belonged – together. You see, a cancer diagnosis has a habit of clearing the decks, silencing the ego, and removing the bullshit we all hide behind at times – it laughs in the face of family trivialities and misunderstandings. I can recall being overwhelmed with both sadness and joy – sadness of the diagnosis and all that we had missed during those years spent apart, yet at the same time a sense of complete and utter joy of being reunited with my little brother once again. I have learned since his death that the sadness and joy we experience in life live near one another. It’s the reason we have so-called happy tears. We cannot have one without the other.

Grief affects everyone differently, and when it comes to siblings, we are often overlooked. In the wake of our parents’ unimaginable grief, it can be difficult to process or even prioritize our own emotions without a sense of guilt. Syd was my brother, not my child, so there were times I didn’t feel I had the right to grieve in the same way my parents did. And how would we all readjust to this new family dynamic without the golden child? Where was my place in the family hierarchy now? Did my remaining siblings feel the same way? And he left behind a son – losing a parent when you’re just twelve years old – isn’t that the worst?

The problem is we often compare our grief when there is no comparison. We must acknowledge, accept, and honour our grief – and the many complex emotions that come with it. We are all unique as human beings – as is our grief. I now know there is no hierarchy of grief. It’s ok to feel whatever comes or to feel nothing at all. We must not judge someone else’s grief or our own. And the rule is – there are no rules.

Learning to live without the physical version of my little brother has been unbelievably challenging. There are many times when I have wanted to give up, throw the towel in, and just give in to my overwhelming grief, but then I remember that his death gave me a precious gift – the gift of a second chance at life and I would be doing him a disservice by wasting it.

So now when I think of that saying Mum used to say, I remind myself that despite Syd’s death, ‘we are all still here.’ – it’s only the form that has changed. We will always be a family of six, and I now answer that sucker-punch question ‘how many brothers and sisters do you have?’ with a proud ‘three.’ – he may not physically be here, but his spirit will always be with me – this I know.

Our paths may have changed but our sibling bond will last forever.

Book recommendations:

‘Sisters and Brothers; Stories about the death of a sibling’ curated by Julie Bentley & Simon Blake.

Published by Unknown.

‘Losing You, Finding Me; one woman’s crusade to save her brother and ultimately herself by Kay Backhouse.

Published by 2QT Publishing.

’The invisible String’ by Patrice Karst.

Published by Hachette Book Group.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Kay Backhouse was raised in the Yorkshire Dales, a picturesque part of the UK. It was here where she developed a strong connection to, and an appreciation for nature and it’s healing properties.At the age of twenty-eight she emigrated to Australia where she lived with husband, Rick, and their children for ten years. Kay now lives with her family in the coastal town of Morecambe in Lancashire. Through her writing, yoga practise and hospice work, she spends most days working with adults and children, helping them to navigate their way through grief and significant loss. She truly believes that we have the potential to overcome any adversity and that the power to achieve this lies inside each and every one of us.

You can learn more about Kay and her book Losing You, Finding me here

Infant & Reproductive Loss Toolkit [Free Downloadable PDFs for Individuals and Professionals]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. Mental health professionals designed this toolkit for individuals, parents, caregivers, and families navigating perinatal and reproductive loss.

Reactions to pregnancy and reproductive loss are as unique as fingerprints. Some can process the experience relatively quickly, while others experience unrelenting pain and grief.

We hope that this toolkit can be used to add tools to your toolbox and offer words of support, guidance, and care as you navigate life after loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Individuals HERE.

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit was designed by mental health professionals for other professionals who support individuals during their reproductive years and beyond.

It contains information about grief and navigating the impact of loss alongside your clients.High-quality grief care includes compassionate and open communication, informed choice and individualized care. Compassionate communication, the most important element, is required in all aspects of care throughout and following loss.

Download the Infant and Reproductive Loss Toolkit for Supporting Professionals HERE.

Practicing Self Compassion while Grieving

Grief is messy, confusing, enormously painful, and never seems to follow a linear path. This is when we need to take care of ourselves deeply, and yet, why is it that this is also when we beat ourselves up the most?

We are good at being compassionate toward others when they are grieving — something especially evident in social media. The outpouring of love, support, and acknowledgment of the loss is substantial and immediate, giving us the opportunity to virtually show up for every single bereaved friend we have ever come into contact with. On the other hand, we are quite unpracticed at giving ourselves that same kind of loving sustenance or self-compassion.

According to pioneer researcher Kristin Neff, at its heart, self-compassion is “treating yourself with the same type of kind, caring support and understanding that you would show to anyone you cared about.” In essence, you honor and accept your humanness by recognizing that you will encounter personal failings and that life is hard at times for everyone, even yourself. Cultivating self-compassion means that you accept that you are part of the human condition and that you are not perfect.

For whatever reason, people still seem to adhere to a notion that there is a correct way to grieve — contributing to the irrational belief that there is something wrong with them.

In addition to all of the grieving you have been doing, it is important to consider engaging in activities that feel replenishing, like recharging a battery. This way you have the energy to continue to grieve. It is perfectly fine if you want to stay home from work one day or decline an invitation. It would also be great if you feel up to going out and having fun. Give yourself permission to experience the good and the bad. This creates the opportunity to normalize the experience and contributes to increased self-compassion.

So How Can We Practice Self-compassion When We Are Grieving?

We can take moments to actively bear witness to our own suffering and fully accept it.

Notice your pain, acknowledge how it feels and that the world, as you have known it, has changed. Even if you can’t provide self-compassion, try to at least recognize that you need some support and care at this time.

We give ourselves permission to be imperfect.

There is no such thing as perfection. Things will not work out the way you want them to all the time and you may not respond in the way you had envisioned. So what if you mess up? Everyone around you has done it before and will do it again, so you are in good company.

We think about what we would say to a friend who has gone through a similar issue, and we say those same things to ourselves, even if we don’t quite believe it just yet.

Write down exactly what you would say to someone who came to you with your problems — and then read it out loud to yourself over and over until it starts to feel familiar.

We think about ourselves.

Putting ourselves first is by no means selfish. It is okay to decline an invitation or take a sick day at work when you are feeling down. It is also okay to practice self-care. This might include limiting self-judgment when we experience positive feelings such as joy. Sometimes people also say things to us that feel distressing, even when we know it comes from a place of compassion. Take care of yourself by letting them know how you feel and what you might need from them instead.

We realize that there is no “correct” way to grieve.

Everyone grieves differently. Sometimes we feel like talking, sometimes we don’t want to talk about our loss at all. Sometimes we think about it every day and other times, we can go minutes, hours, or days without thinking about it. Sometimes we just want to go out and have fun with our friends or family. Grief is complicated — just know that you are doing the best you can.

We notice when we are being overly harsh or critical of ourselves.

We sometimes feel that we need a critical voice to get motivated, that by beating ourselves up we will “do better” in some way. We also might beat ourselves up and focus on feelings of guilt because it feels easier than attending to our pain. Self-compassion is about being okay with who you are and how things are unfolding. Just notice when this is happening, and try to soften your response.

We take breaks from social media.

It might feel too much for us at times, especially during anniversaries or birthdays, and we may need to unfollow our loved ones on social media until we feel emotionally ready to go back to it.

We seek professional help when we need it.

Therapy is not a sign of weakness or that something is wrong with you. Sometimes, we just need a little extra support.

We cultivate hope.

A major tenet of self-compassion is recognizing that our suffering is part of the human condition. No matter how hard things are right now, you are not alone and will get through this.

We forgive ourselves for not doing any of the above.

Pet Loss: When People Fall Silent

A few days after the birth of my younger brother, my father was taking the dog he and my mother adopted from the humane society, along with my twin and I, to the veterinarian. Years later, my father would share how many times he wiped his eyes on the car ride there. Yoda shared 16 years of her life with my parents. She was there when they went from a family of 3 to 5, and at my mother’s side as we were preparing to welcome our younger brother.

Clifford was just under a year old at the time we said goodbye to Yoda. He and my mom were thick as thieves. He’d keep her company while we were at school, dad was at work, and in her most difficult moments as her cancer progressed.

Clifford was about 9 years old and had a history of health complications before my mother’s death. After her death, we knew he was grieving too. He would search her out, but he began to slow, and other health factors started to creep in. We were just starting to thaw out from the depths of our mother’s death. And now another loss six months later?

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Photo of Jessica’s mother Terry with her dog Yoda.

Both are sitting on the stairs Jessica’s mother is smiling for the camera holding Yoda in her lap

Why do we question ourselves, and our grief when it comes to pet and other animal losses? Grief is the natural response when we face the loss of something or someone we have a connection to. The grief we feel after a pet dies is a natural response to their loss given the unique relationships we have with our pets. The humans in a pet’s family may be the only ones they know and love in their lifetime. We can experience grief bursts as we navigate this loss: instead of our grief showing up when our loved one no longer walks through the door at 6:00 pm after work, it may be each time we come home and don’t hear their paws hitting the ground as they race to greet us.

Roxy was our first dog a few years after Clifford and my mother’s death. It also felt strange: excited to have a dog again, while also feeling pangs of grief for Clifford. We can hold space for new love, while also still experiencing moments where we miss our old pets who we loved just as equally.

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

photo of Roxy, a white dog with curly fur laying on her side on a wood floor holding a stuffed sheep

When Roxy was 13, our vet had noticed changes in her health typical for a dog her age. Every time I came home to visit I’d savor my time with her, and wonder, “Would this be the last time?”. A year later, Roxy was now no longer eating or drinking as often, and the vet felt her decline was her way of telling us she was ready to go. She indulged in poached salmon for her final dinner. Early one summer afternoon, my dad sent our family a photo of him lovingly holding Roxy in his arms and looking into her eyes. The note said she had passed onto the rainbow bridge, and he gave her extra hugs from all of us. I held space for the relief that she was no longer in pain, and the grief that I would never give her a belly rub again.

These are just some of my stories, and those reading this may have stories too. The tales where they did something ridiculous. The time they were there for you in your highest highs and lowest lows. The first time you met them. The last time you held them.

It’s important we hold space to share our stories but it can be difficult when pet and animal loss is a form of disenfranchised grief. Disenfranchised grief refers to when society denies a griever’s right, role, or capacity to grieve. This can leave us feeling even more isolated as we grieve. North American settler culture tends to prioritize human death loss over animal loss. But that doesn’t make your grief any less valid. Your grief may come in waves, be gentle with yourself as your body goes through this natural process.

You may experience shadowlosses and secondary losses related to the death of your pet.

I felt a pang when I didn’t hear the clinking of Roxy’s dog tags, expecting her to slowly saunter into the hallway my first visit back after her death. My parents felt lost with what they should do with pet care supplies they couldn’t donate. Many friends where I live have pets and I was able to share some of Roxy’s most treasured items with them, something Roxy would appreciate. But the choice tugged at my heartstrings as I removed these items from my family home.

Each unique bond with our pet is carried within us and you are allowed to honour it in whatever way makes sense. It may be having photos of your pet up in your space. Honour old traditions of your old pet with your new pet – if or when you choose to welcome a new pet into your life. Share stories of your special furry, feathered, fluffy, or scaly pet with your circle. Our stories can help us feel connected to them, and also feel less alone in our grief.

There is no right or wrong way to grieve, only yours.

______________________________________________________________________________________

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW . Grief Stories Healthcare Consultant

Jessica is a registered social worker and owner and of Cultivating Connections. Her expertise includes helping individuals and families facing anticipatory grief, ambiguous loss, disenfranchised losses, and sudden deaths. Jessica believes in the power of connection; within ourselves, with those who have died, those we are in relationship with, and with our greater communities. Through sharing our stories of grief and loss, we tend to our connection with those who have died and creating connections with others.

Jessica is a white woman living on the traditional territory of the Anishnabek, the Haudenosaunee, the Attiwonderonk, and the Mississaugas of the Credit peoples, also known as Guelph, ON.

Making Space to Hear Them: supporting children in grief

By Alyssa Warmland

Children tend to be naturally curious as they grow and learn to navigate the world. As adults, it’s our job to walk with them through that process of learning and to support their curiosity. It can be hard to do that with respect when we are situated in cultures that don’t acknowledge children as autonomous humans worthy of mutual respect. It can be tempting to encourage kids to ignore their feelings about death and grief or to shut down conversations about it when they ask questions. Sometimes, this is because we just don’t know what to say that is developmentally appropriate, especially with young children. Sometimes, it’s because we haven’t allowed ourselves to develop our own thoughts and feelings about death and grief and it feels uncomfortable for us to talk about.

What grieving children need from adults in their lives is to feel heard, just like adults do. When a child asks questions or talks about death or grief, here are some ideas of things to say and how to prompt conversations that allow us to listen:

– Tell me more about your ideas about dying. What do you think happens after someone dies? Those are good ideas, thanks for sharing them with me. I think [insert your own cultural or family beliefs about death].

– How are you feeling about [the being the child is grieving]? Do you want to tell me about some of your favourite memories about them? It’s okay to talk about it.

– It’s okay to feel however you are feeling. It’s okay to feel scared or curious about dying. You’re not alone. Do you want to tell me more about what’s going on for you? I love you and I’m here for you.

– Death isn’t something people can control, I want to make sure you know it’s not your fault [person/animal] died. Sometimes things just are and we can’t do anything about – them, but we can talk about how we are feeling about it.

It can also help to read children’s books about grief. Even if you don’t read them with your children, they might help give you the language to talk with them about death and grief when you’re not sure what to say. Most professionals recommend using direct language, such as “death”, “dying”, and “grief”, rather than terms like “passing away”, because they are easier for children to understand.

It’s important for children to know they’re not alone in their feelings and that it’s okay to feel hard things with the adults in their lives. Humans are social creatures who crave connection. Even when it’s hard or uncomfortable, pausing our busy lives to make that time for connection with children is important so they can learn how to process grief or whatever other feelings they’re having. It can also be an opportunity to re-parent ourselves. It might help to ask ourselves why we feel uncomfortable with a topic and what our own inner child might need to hear about the feelings that come up for us about death and grief. It’s important to seek out connection and space to process those feelings too, whether that’s through therapy or with other adults we trust to be vulnerable with.

Grief literacy and emotional literacy in general is worth making space for. Children have valid feelings worth expressing and being heard it’s it’s okay to stumble, imperfectly, within those conversations with them. Being with them is what is most important.

Additional Resources:

Kid’s Grief

Kids Help Phone

Children’s Grief Foundation

Children and Youth Grief Network

Children’s Grief Colouring Book

National Alliance for Children’s Grief

Bereaved Families of Ontario

Camp Erin

The Dougy Center

Kids’ books about grief:

When Dinosaurs Die

Badger’s Parting Gifts

The Fall of Freddie the Leaf

The Invisible String

The Heart and the Bottle

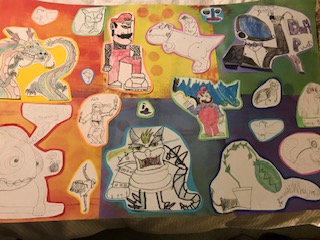

Doodles

By Betsy Fisher

Surviving.

Wading into all the “firsts” I never wanted to see.

On the first anniversary, I invited people who would understand – friends who knew Marshal’s love of art, and his creative spirit. They all came.

I had copied several of Marshal’s doodles of incomplete characters and creatures, with some finished for the kids to color. I eagerly watched to see which doodle or drawing each person chose.

“Hey! That looks like Abraham Lincoln! I want to finish that one.”

“Cool…look at this giraffe! I want to color this one!”

“Whoa, what a cool monster!”

“What is this one?! I think it’s some kind of frog.”

The children sat in the kitchen table or on the porch, clutching crayons with great care and the grownups chose doodles and pieces of something larger, saying, “Oh, yes, Marshal would have loved this.”

People smiled as they drew or colored. I found myself smiling, too, even laughing now and then. I walked among them and as I watched them, I felt things I had not felt before, things I could not name.

I had stressed over “what to do” to mark this date, one year later, where ending and beginning would meet. Marshal took ordinary, simple things, and created magic.

Among the many doodles was one of a man-eating plant. A Venus Flytrap like the one from “Little Shop of Horrors” but with a face and personality of its own. It is stretching over and about to swallow up a stick figure. “Oh snap!” says the figure. “Why me?!”

An 8-year-old boy chose that drawing to color. The little hero had miraculously survived cancer as a toddler, and now he was a full-on, healthy, nothing-but-smiling little boy. We met him, and his mother, at Shands, and we grew to know and love them well in the years to follow.

He remembers Marshal a little – his famous fart sounds, character voices, and artistic creations. Their shared love of Mario. He carries his lunch to school today in Marshal’s Mario backpack. He was so excited to get started.

His picture was so colorful and he showed it to me with such pride. I told him more than once just how much Marshal would have liked what he had done with it.

They all seemed to know how important it was to me. They seemed to know Marshal would be there, too. And he was.

As I took it all in, Marshal seemed so strangely present. I felt a different “alive” than I had felt in that first terrible year of grief. He was my smile, the lump in my throat with every hello and goodbye. He was the twinkle in my eye as I saw their love, as I immersed myself in this afternoon.

I hadn’t been sure I could handle the laughter, or making this saddest of days a happy one, somehow. But I could, and it was.

Many of them left their doodles for me to keep or sent pictures after finishing them at home. A friend took them all and made a simple collage, now in my room.

It is love carrying on. It is my proof. Living proof that just as more can be made from these incredible beginnings of doodles and sketches, more can be made from my story with Marshal. Maybe I can move forward, bringing him along with me.

Legacy. Life. Continuity. Connection.

Always and every day.

If you’d like to draw and color with Marshal’s doodles, email Betsy at marshalsdoodles@gmail.com.

Grief Busting Zine [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. We’re sorry you’re feeling this way right now but so glad you’re reading this.

This zine is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

Physical copies of this sine were originally distributed at Cultivate Festival in 2023.

Community Grief Toolkit [Downloadable!]

Navigating life, death, and loss can be overwhelming. This toolkit is designed by mental health professionals and contains information about grief, different types of grief we may experience, gentle reminders on how to move through grief, as well as tips for those who may be supporting someone in their life who is grieving.

This toolkit also reflects on how we support grief in the community. The tools to come together and honour our collective experiences and how to build the resources for further support.

Jessica’s Reflections as an Adult Grieving Child

By Jessica Milette, MSW, RSW

November is considered Bereavement Awareness Month, and this year November 16 commemorates Children’s Grief Awareness Day. 1 in 14 children in Canada will experience the death of a parent or sibling by age 18.

The first funeral I attended was at the age of 7 when my Nana, or paternal grandmother died. My family buried my maternal grandfather 7 years later after he experienced a stroke when I was 14 and my mother was still in treatment for cancer. 13 months later, I would be burying my mom at age 15 after dying of cancer. She was 49. We would be gathering again less than two months later to bury my godmother and aunt who died suddenly and unexpectedly. Every time I felt like I had found footing on the shores of my grief, another loss would crash over me like a wave, dragging me out to a sea of unknown.

Navigating puberty can be an exciting and challenging transition in our life that also can have us feeling grief from non-death losses as we figure out who we are becoming. Not only was I trying to make sense of hormones and changes during this time of life, but my mom – the person who I would have gone to for support was no longer a phone call or hug away. Parents or trusted adults are people children often turn to for support, but my circle of trusted adults was shrinking. My peers were focused on what to wear on civvies day (a day where we didn’t have to wear a uniform), while I was focused on just surviving.

I felt so alone in my grief, although my twin, younger brother, dad, and other relatives in my life were also grieving. Friends would try to show up for me, sometimes it didn’t land well. There are friends who had never been to a funeral that walked with me in the depths of my grief who still hold a special place in my heart and life. I felt like I was in a sea of students in the hall between class with a flashing neon sign that read “Human with all the dead people in their life”. At times I could tell how awkward both peers and adults in my life were when approaching me – what do you tell someone when you’ve never experienced a death? And the person who is grieving can’t even legally drive a car!

There was no right or wrong way for me to grieve, but I had to find my own way to grieve. Sometimes they were helpful, and other times the things I did I thought helped me with my grief were not so helpful.

I am fortunate that despite the not-so-careful caring people in my life that made me feel invalidated, I had many caring adults in my life who let me know that grief is natural, and let me share stories of my loved ones. Within the first year of our loss, each of my siblings, my father, and I attended a grief support group. Walking into my first group was both scary and exciting: other teens like me?! The peer volunteer who co-ran these groups was actually someone I knew personally, but had no idea that they had been touched by death too.

I felt deep sadness, guilt, and anger in that group. I also felt deep connection, joy, and even laughter. We got to talk about our sibling, parent, or other close person in our life we were grieving. Talking about grief didn’t make me feel more alone, or worse, it made me feel LESS alone. That we all grieve what we are connected to. That’s it’s okay to not be okay. That sharing our stories of our person and our pain can be healing when we have the right kind of listener in our corner. And that we never have to walk alone at any age or stage of our grief.

Ghosts From The Past

By Josh Abel

I met Holly riding the bus in our community. She is very attractive with a winsome smile and piercing eyes that I would trade anything for. She was also the bus driver. At that time Holly went to school to become a nurse. After becoming a nurse, Holly didn’t drive the bus that much, but one of her fellow bus drivers mentioned to me that one of Holly’s patients had died and it had a negative impact on her. It brought back ghosts from my past as I also had a job in which people died which had a negative impact on me.

I used to help people deal with their addictions. One former client relapsed and overdosed leaving a one year old child behind. I couldn’t begin to describe how sorry I felt for that one year old. Then there’s the second guessing (guilt). Could I have done more and why didn’t I see this coming? Another former client on one Mother’s day killed two of his next door neighbours. Since that time, Mother’s day has never been the same for me. I felt similar emotions for the family of the two victims. My heart went out to them and although I never met them, somehow this was one of those occasions where saying sorry just isn’t enough. The police did catch my client who wasn’t “at risk” (he came from a nice home, wasn’t involved in gangs) of committing such a crime but it still got to me anyway.

As a caring person, those incidents affected me just as Holly’s affected her. You just can’t take the human part of you out of the equation. I did tell Holly I was sorry for the loss of her patient. Holly is also a caring person and I don’t want her to experience the same negative impact as my situation did with me. They can teach you every aspect of how to perform your job except one: how to deal with second guessing. The guilt will get to you if you let it, especially if you are a perfectionist at your job. Your work ethic teaches you to be the best at your job, but there are things you are going to encounter that you just can’t control. When I started my job I wanted to help people I wanted to make an impact on people’s lives, an idealist. In my case that’s what made the guilt even more of a challenge to overcome. Although I can’t control someone else’s behaviour, Mother’s Day will never be the same for me especially since my own Mother passed away last year.

Holly if you’re reading this you are going to have a lot of success in your job and you probably won’t give it a second thought. Please give the successes more attention than the failures because that’s what makes the job enjoyable (helping people).

Holly’s true reflection is beauty and she made the bus fun to ride.